This is the transcript of a talk I gave at Re:publica in Berlin at the 9th of May 2017. You can find all the slides in that insanely fast GIF up there as PDFs on Github. You can also find a video recording of this talk on YouTube.

Hi! This is me, and every single one of you:

We’re standing on the ground of hard facts. (“Der Boden der Tatsachen”, as Germans would say.) Well, ok, there are no hard facts; let me rephrase that: We’re standing on the ground of concepts with different levels of certainty; concepts entangled by confidence intervals. For example, it is a kind-of-certain fact that approximately 97% of climate experts agree that humans are causing global warming.

When we’re accepting a “fact”, we start to believe in it. Eg we can believe that global warming is real. Beliefs are important: They let us marry people, let us found companies and research projects, and let us go to church every Sunday. And beliefs are the basis of every ethical discussion: We need to agree on what’s happening before we can discuss what we should do.

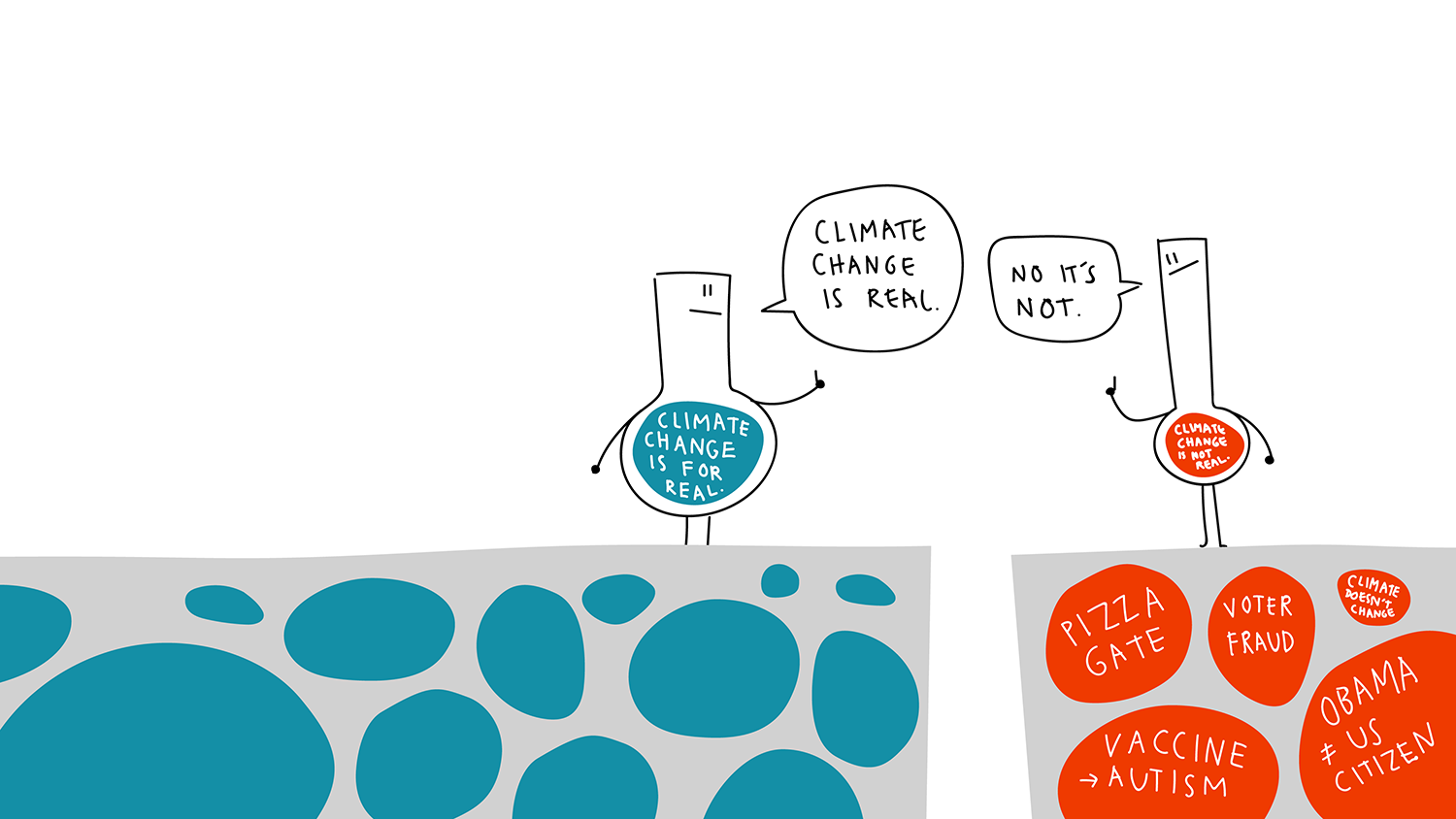

But it seems like in more and more cases, we don’t have a discussion of what we should do – but what is true in the first place. What is really happening? What is truth? What is reality? What are the facts? It almost seems like some people stand on the ground of a completely different reality; sharing completely different facts. But of course, that’s not the case. The reality is still the same, pretty much.

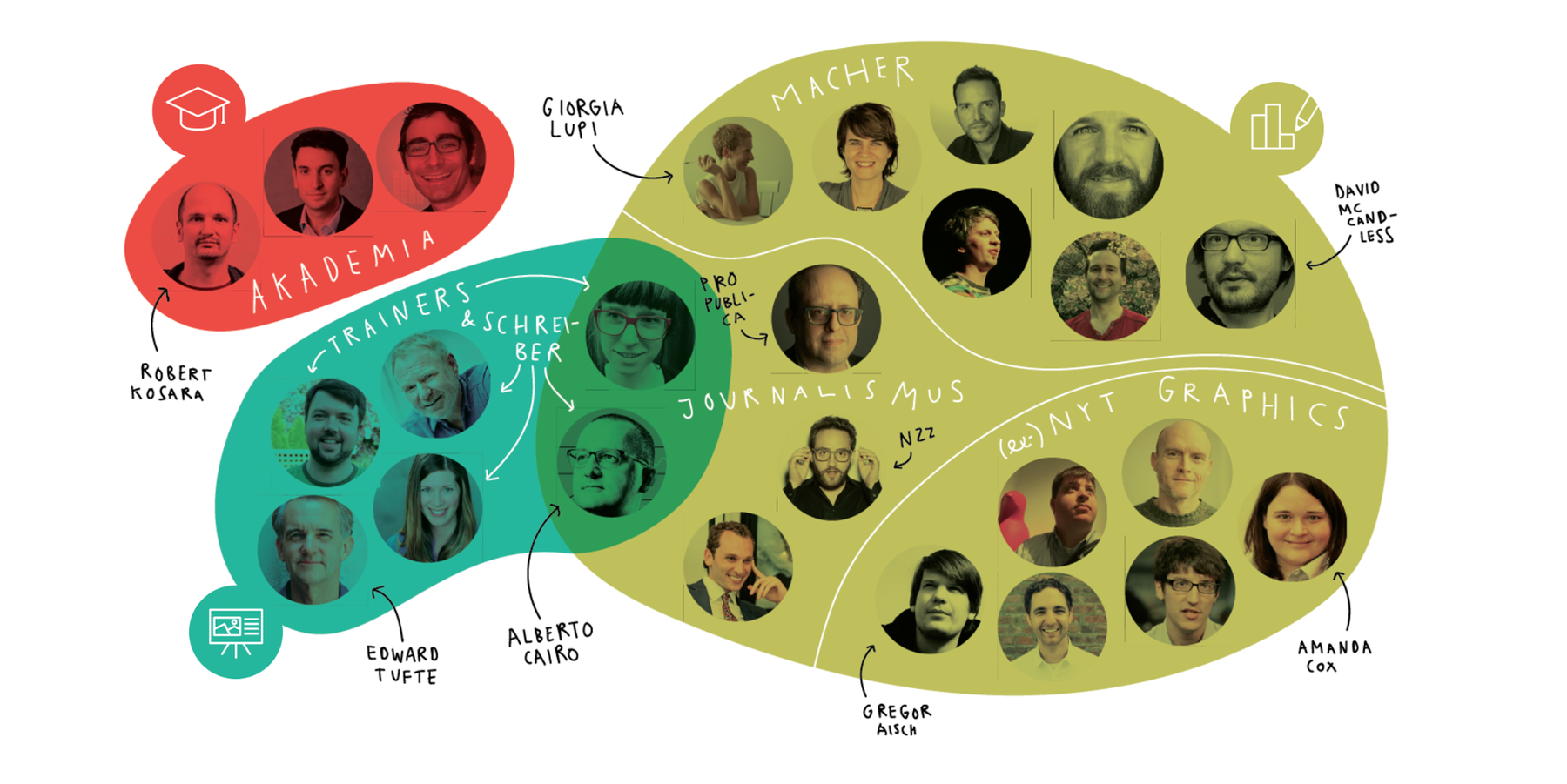

What I’m currently doing with my life, is visualizing the facts. I’m visualizing data, often from the Census or Scientific Studies. And then I’m communicating it to the public and say “Here, look, these are the facts”; let’s have a discussion on these grounds. So when people don’t take them seriously, I have a problem. I’m not doing my job well.

Today I want to explore how I can do my job better. Am I just preaching to the choir with my data vis? Or is it possible to convince somebody with facts, numbers, science, reason?

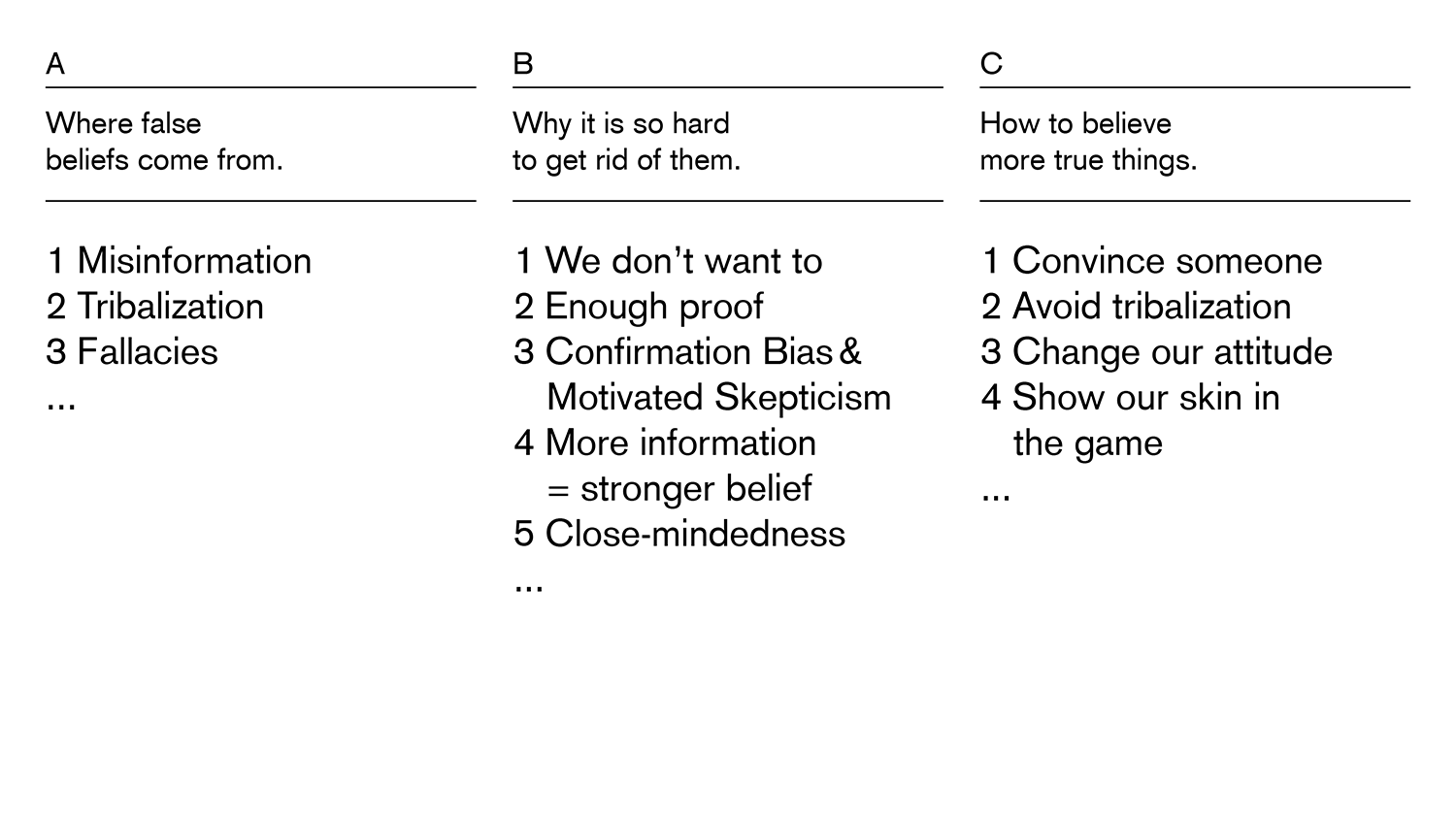

To do so, I will explain first where false beliefs actually come from. Why don’t we all believe in the same? Then I want to explain why it’s so hard to get rid of false beliefs once they’re planted inside of you. And then we’ll use this knowledge to explore what we can do to believe more certain things – we in this room, and I as a data vis person.

A. Where false beliefs come from.

Let’s start by talking about the reasons for false beliefs. Of course, there’s only one:

Fake News is something a lot of people have talked about. (One of the best things, in my opinion, can be found on First Draft News.) I actually think that sharing fabricated content and misinformation on social media is only a minor cause of having false beliefs, but a major symptom.

One of the actual big reasons is tribalization. We’re social animals living in different tribes (our family, our friend groups, our favorite online forum, our Twitter feed). And for social animals, social support is more important than believing the truth about something that’s far, far away like climate change.

In the first instance, beliefs can become a marker of identity. We believe what our family and our friends told us. When we share articles on Facebook, we want to demonstrate who we truly are. We want to define ourselves. “Defining” literally means “to limit, to bound”: We draw boundaries around our identity, also to attract like-minded people.

Showing who we are is especially important to demonstrate whose team we are on. We want to show the other tribe members (friends, forum, party, church) that we are good members of the tribe.

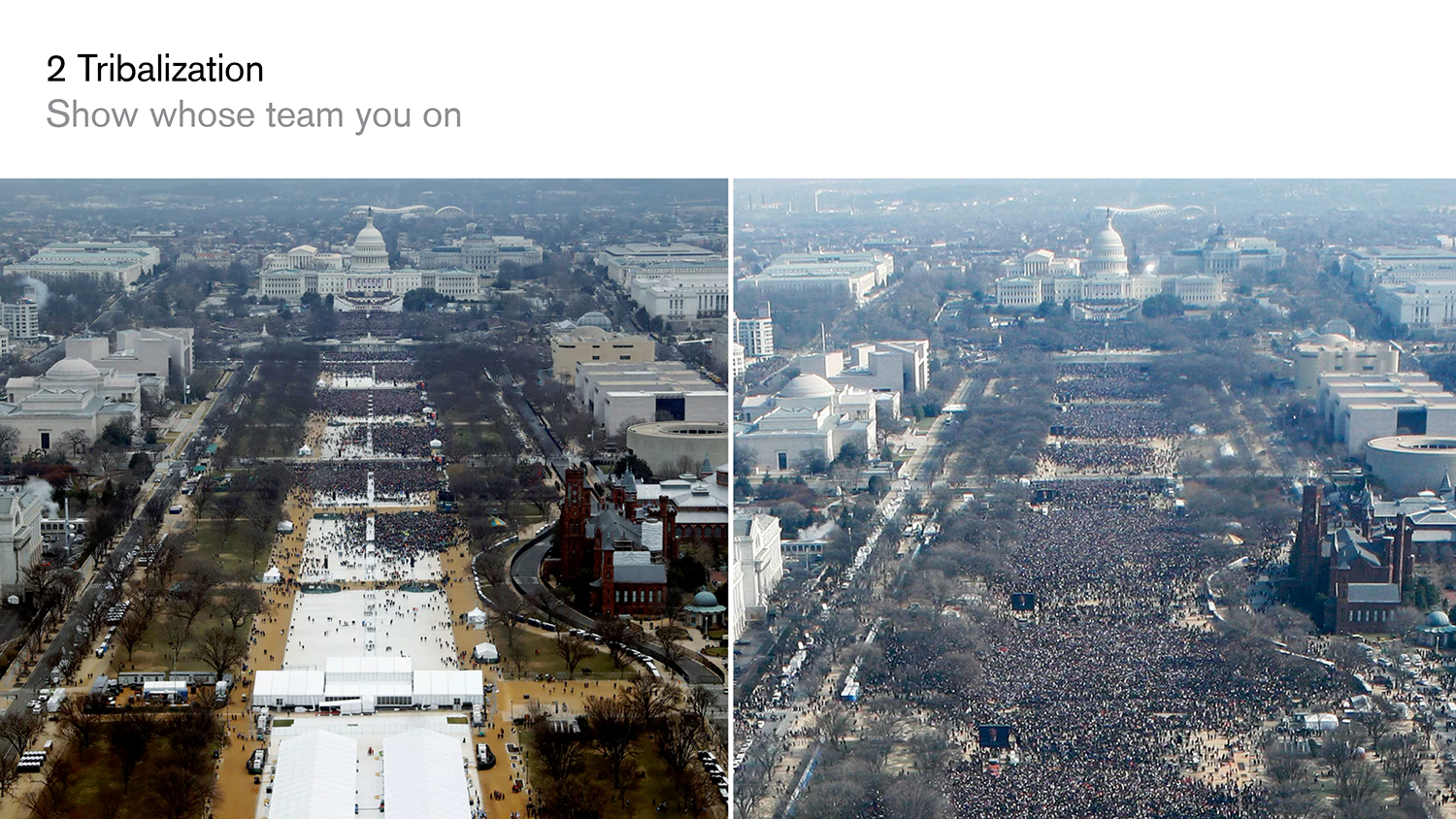

We could see that especially well in and after the election. When confronted with the photo of Obama’s inauguration from 2009 and Trump’s inauguration from 2017 and asked which photo had more people, lots of Trump supporters gave the wrong answer. They said that Trump’s inauguration hosted more people. Not because their perception was flawed. But because it was a way to show their support for Trump. It’s not truth vs lie, it’s their team vs the other team.

But showing off your beliefs with information doesn’t just gain us the trust of a team. It’s also a test to see who WE can trust. These people who unfriended us after we posted a long essay about how much we hate Trump? Yeah, it’s good they’re gone. We’ll definitely not drop by their birthday party this year.

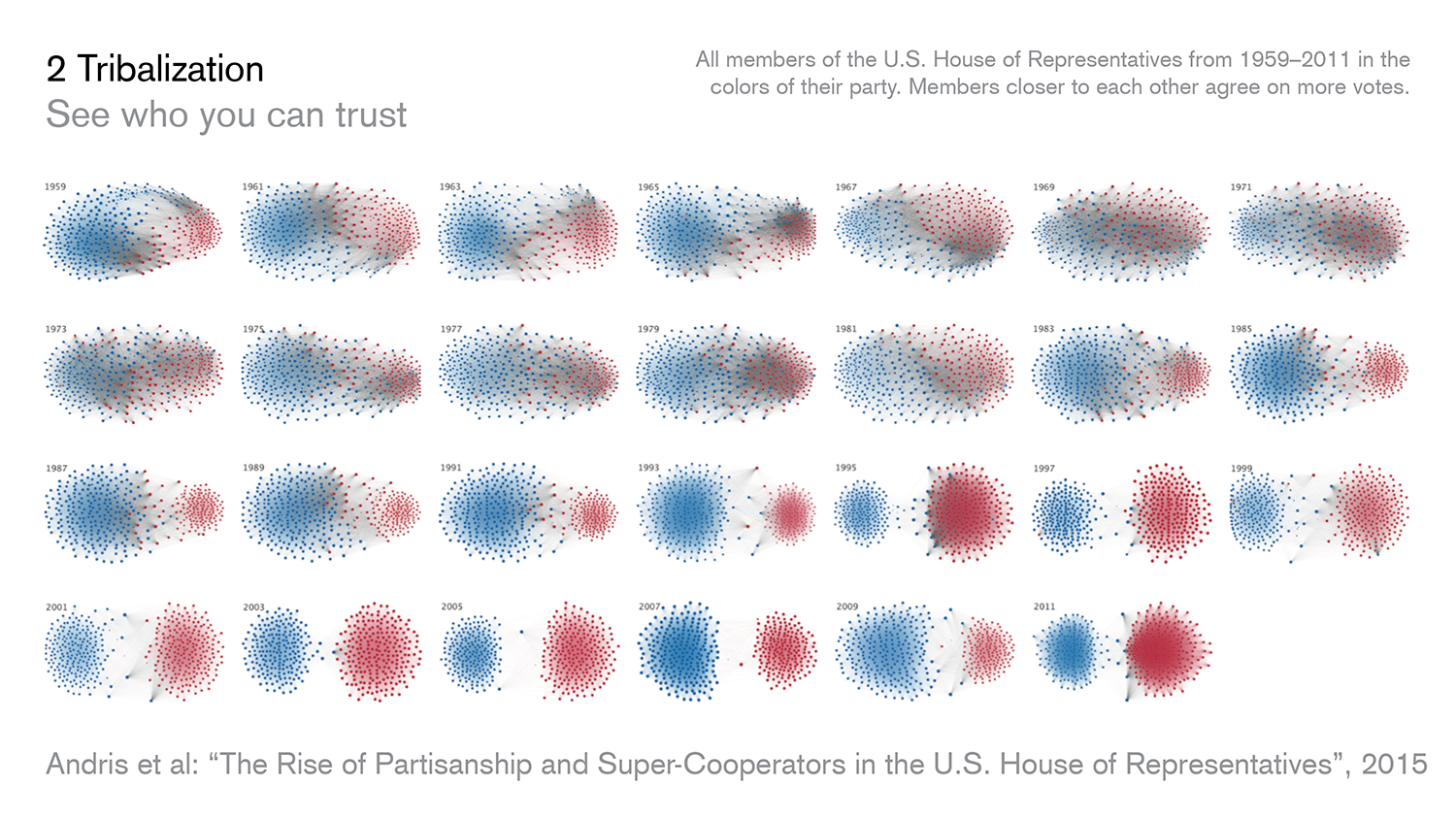

Sadly, that happens more and more in the two-party system in the US. It’s one thing that less and fewer government people agree with members of the other party:

It gets disturbing when you hear that 58% of Republicans and 55% of Democrats had a very unfavorable attitude towards the opposite party in 2016; up from 21%/17% in 1994. Fewer Democrats marry Republicans and the other way round. People of the two parties don’t trust each other as much as they did only a few years ago.

Interesting enough, for forming beliefs for the sake of tribalization, it doesn’t matter if we understand what we believe. They are too far away from us. Ask yourself: How does climate change work…exactly? Could you explain it? I know I couldn’t. But people from my tribes and I believe in it, and we know someone is from another tribe if she or he doesn’t.

The third reason for forming false beliefs I want to talk about is fallacies. This could be a talk on its own, so I will just mention one example: Generalising from anecdotal evidence. Which means seeing one instance and applying that to the whole concept. Saying “Man, it’s so cold and rainy for May. Global warming, yeah right” for example:

B. Why it is so hard to get rid of them.

So once we got a false belief, we just keep it until somebody comes and says “Dude, that’s not right”, and then we get rid of it – right? Unfortunately not. We defend many beliefs like crazy.

Since we get so many beliefs from our tribes, questioning the belief means questioning the tribe. Beliefs are connected to the person who gave it to us, the situation we’re in, the memories, our upbringing, etc. If a belief turns out to be untrue, then all of this is in doubt.

But there’s no need to get rid of the beliefs anyway. One quick Google search tells us that there is tons of evidence for our belief, and our tribe confirms us on a regular basis. And if one online forum tries to convince us of the opposite, we can just leave and can go to another one. The internet is truly a paradise for finding confirmation.

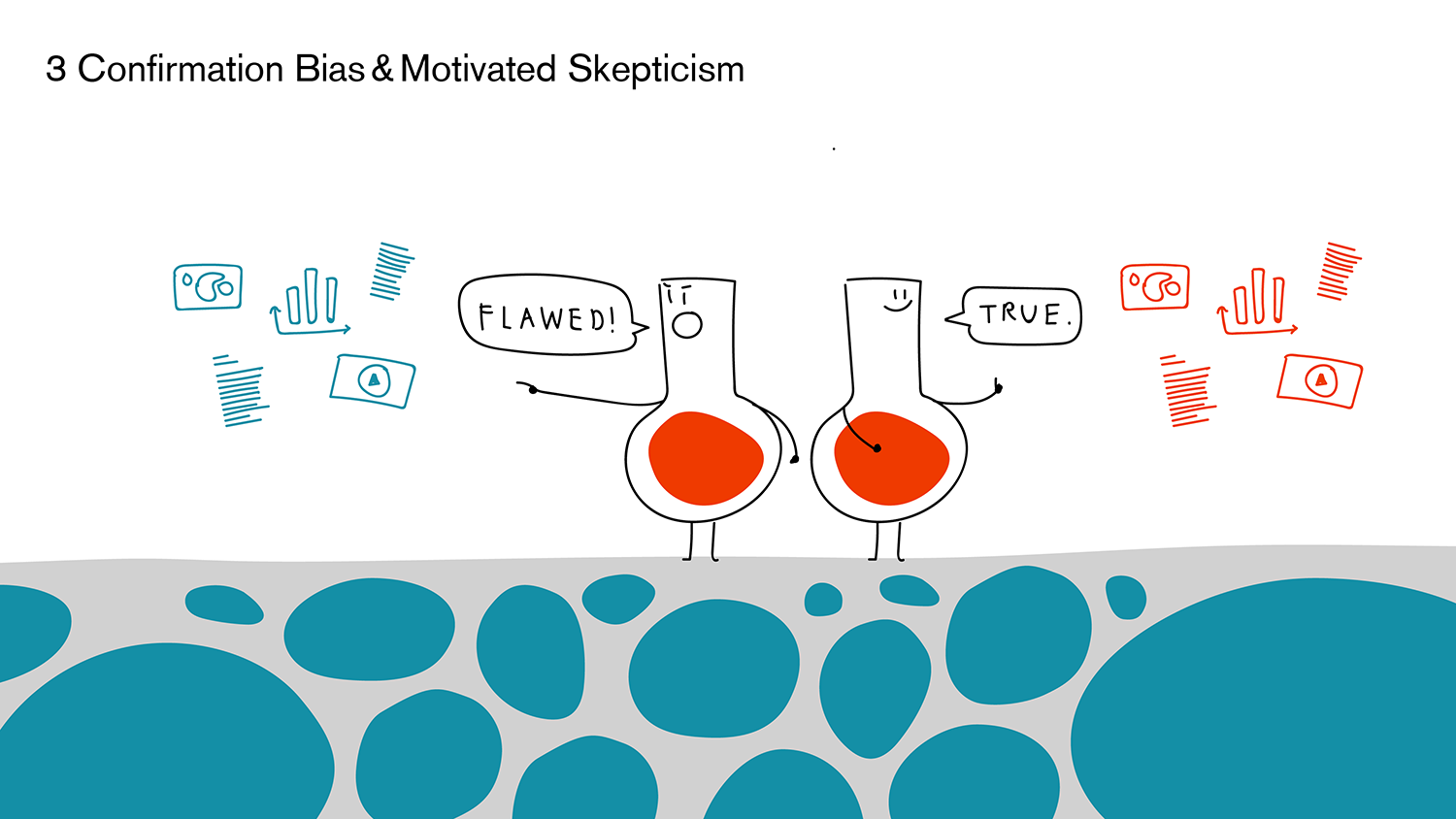

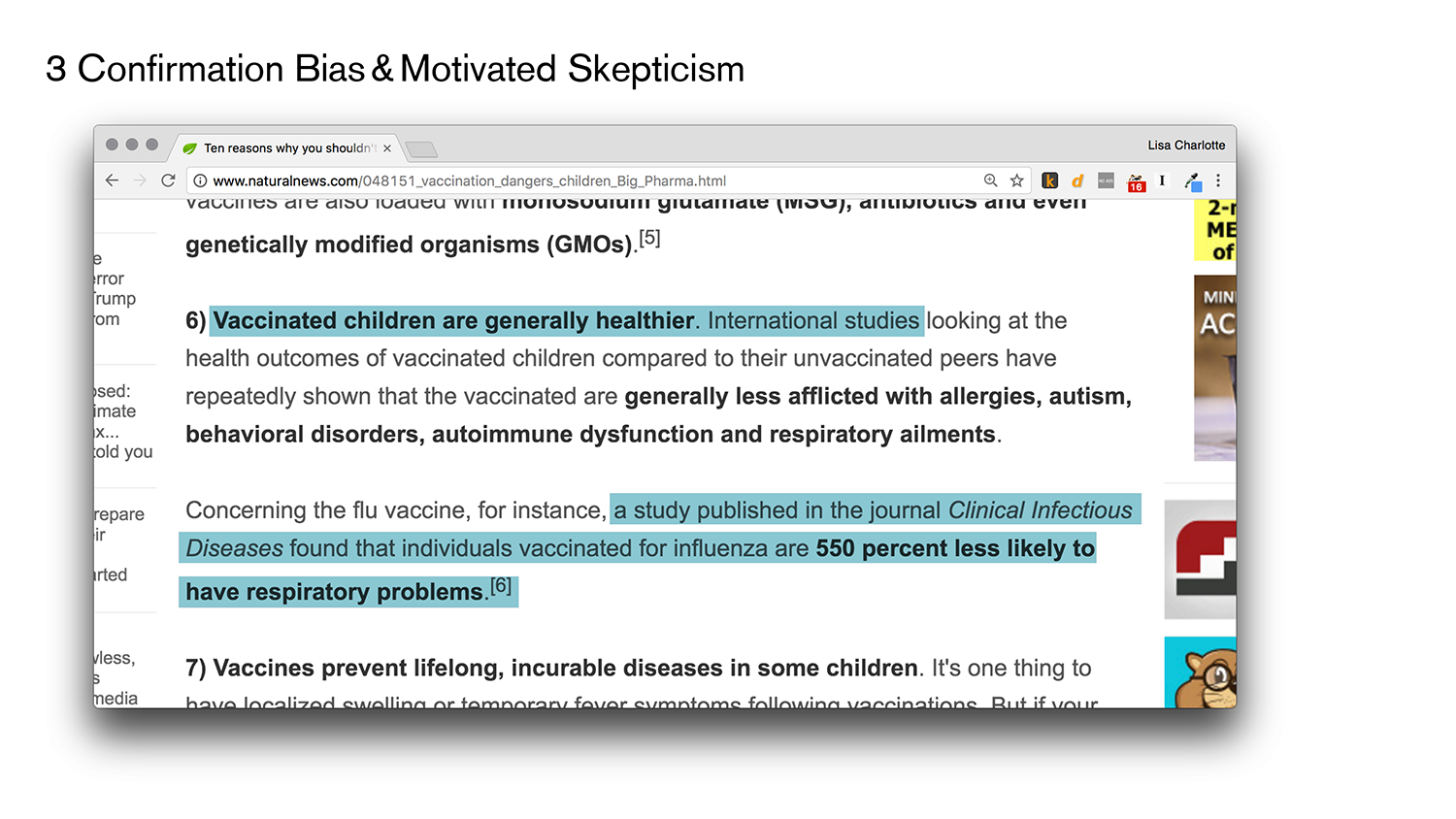

Once we have a belief, we perceive information differently. Information that confirms our beliefs we agree easily with; we question it less and remember it better. The opposite of this Confirmation Bias is Motivated Skepticism: When we get confronted with information that opposes our beliefs, we apply more skepticism than normal. Everything seems untrustworthy suddenly: The author, the sources, the medium.

An example of that can be found in the following article, which explains why you should vaccinate your kids. As somebody who agrees with the premise, I also don’t question the sources: “International studies”, it says. Sure. And there’s this one study that basically explains that you have less respiratory problems when you don’t have the flu? Sounds about right:

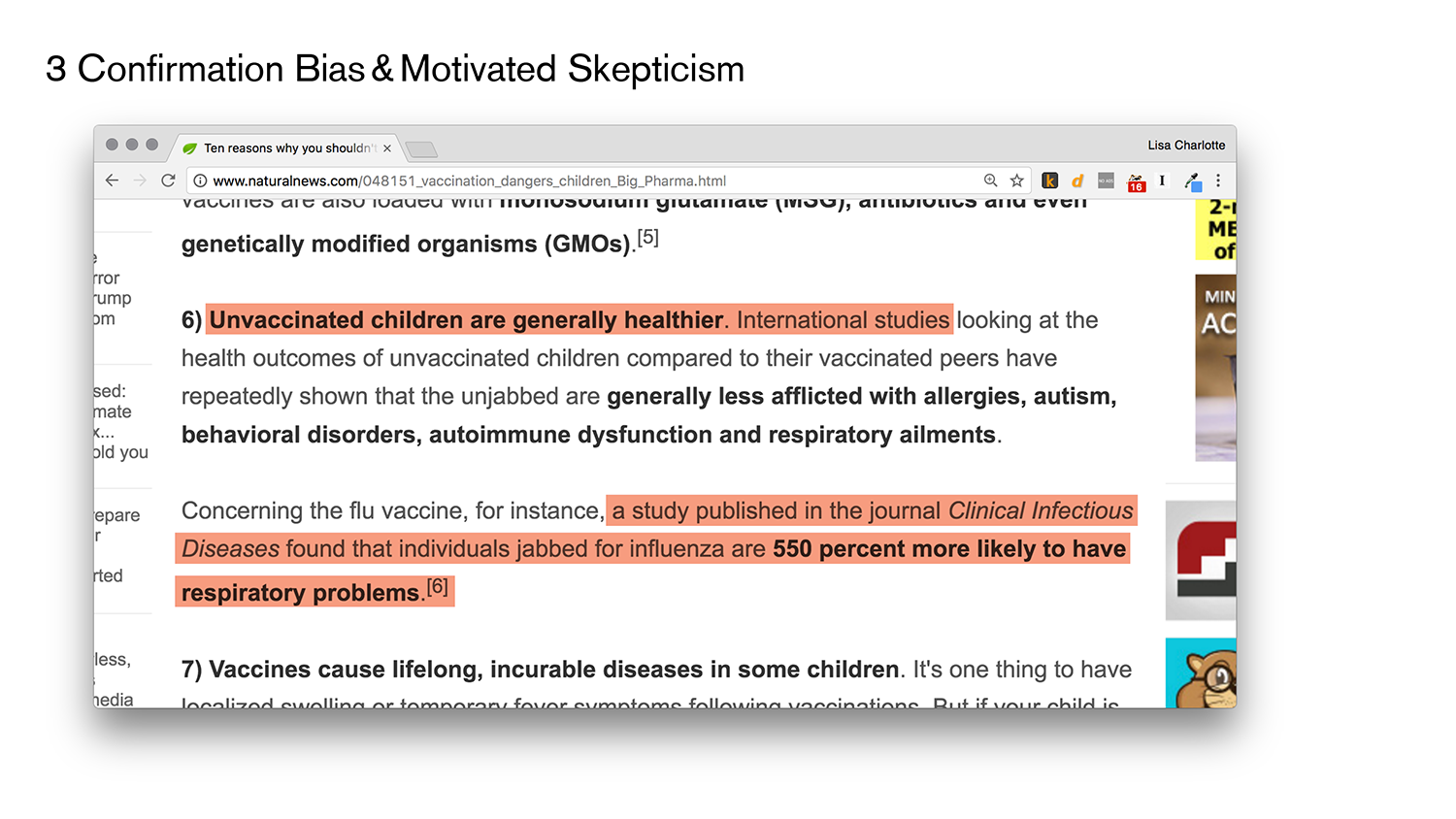

Ok, fine. I’ll admit, I changed the original article a bit. The actual article can be found here and speaks against vaccines.

And suddenly every second word makes me angry and suspicious at the same time. “International studies”? Yeah right. I know what kind of studies THESE ones are. Certainly not peer-reviewed, I bet. And this journal called “Clinical Infectious Diseases”, they mention? I’m sure it has a super bad image in the community. I wouldn’t trust one article published in there. And naturalnews.com? Well, I’ll certainly unfriend everyone immediately who mentions this site on Facebook.

Confirmation Bias and Motivated Skepticism don’t just make us perceive information differently, but also strengthen our beliefs – in both directions. Consuming lots of confirming information (more investment) nourishes my belief:

It’s supposed to work also the other way round: If you show me information opposing my belief, my belief will become stronger. You might have heard of it as the Backfire Effect, but it’s not well proven scientifically. I dare you to find a good paper and I’ll change this blog post.

Close-mindedness is the last reason I’ll mention today. Some of us are it more, some are it less: We are different people, and some of us accept opposing information better than others.

I think it’s important to keep that in mind, to not give up on people (“Whyyyyy the heck do you not accept the truth?”).

C. How to believe more true things.

So after hearing about the obstacles that keep us from believing more true things…how can we still attempt to do so? The most obvious idea is to convince someone, brute force: “Hey, you believe x, but that’s not true. You should believe y.”

Often, that’s neither the most successful nor the kindest attempt. Let’s maybe not do that.

Instead, we can try to make them see the truth themselves. We can ask them questions (like Socrates back then): Why do you believe what you believe? How did you come to that conclusion? What would be the consequence of your thinking?

And we can point out the difference between the facts and their beliefs in a subtle way.

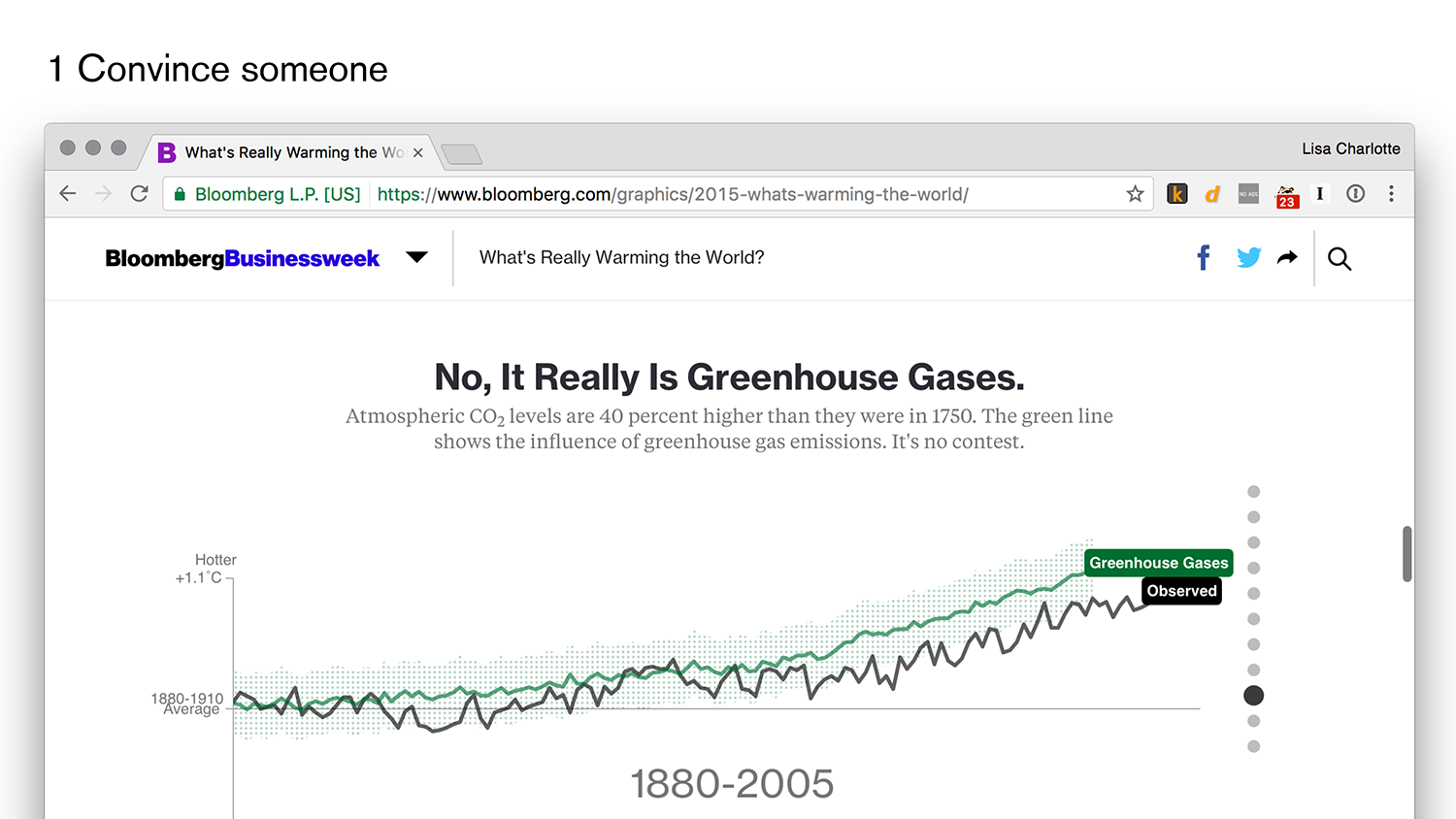

The closest data visualization I’ve seen to this approach is Bloomberg’s “What’s Really Warming the World?”. It leads through different factors that “Climate Deniers” see as reasons for climate change: Is it sun activity? Deforestation? Ozone Pollution? No, it really is greenhouse gases.

The next idea, actively avoiding tribalization might be the most powerful approach against false beliefs, especially when we believe that tribalization is one of the main reasons in the first place. The easiest way to avoid tribalization is to find people with different opinions, and then to actively listen to what they have to say. Why do they believe the things they believe in? What are their rational reasons?

The German ZEIT Online is attempting conversations like that. Right now they have a call for people who want to meet different-minded people in their neighborhood, on one afternoon in June.

During such conversations we can try to build understanding and empathy, which might let us discover some hidden truths and emotional reasons:

The third way to make us believe more true things is to change our attitude; towards ourselves and towards others. This attitude shift can happen in different ways.

We need to accept that there are millions of facts we don’t know, that not knowing things is normal (not devastating); that changing beliefs, therefore, is necessary to grow. Which means that having beliefs as a marker of identity is not the most marvelous idea. Our beliefs come and go to help us act in this world; but we are not defined by them:

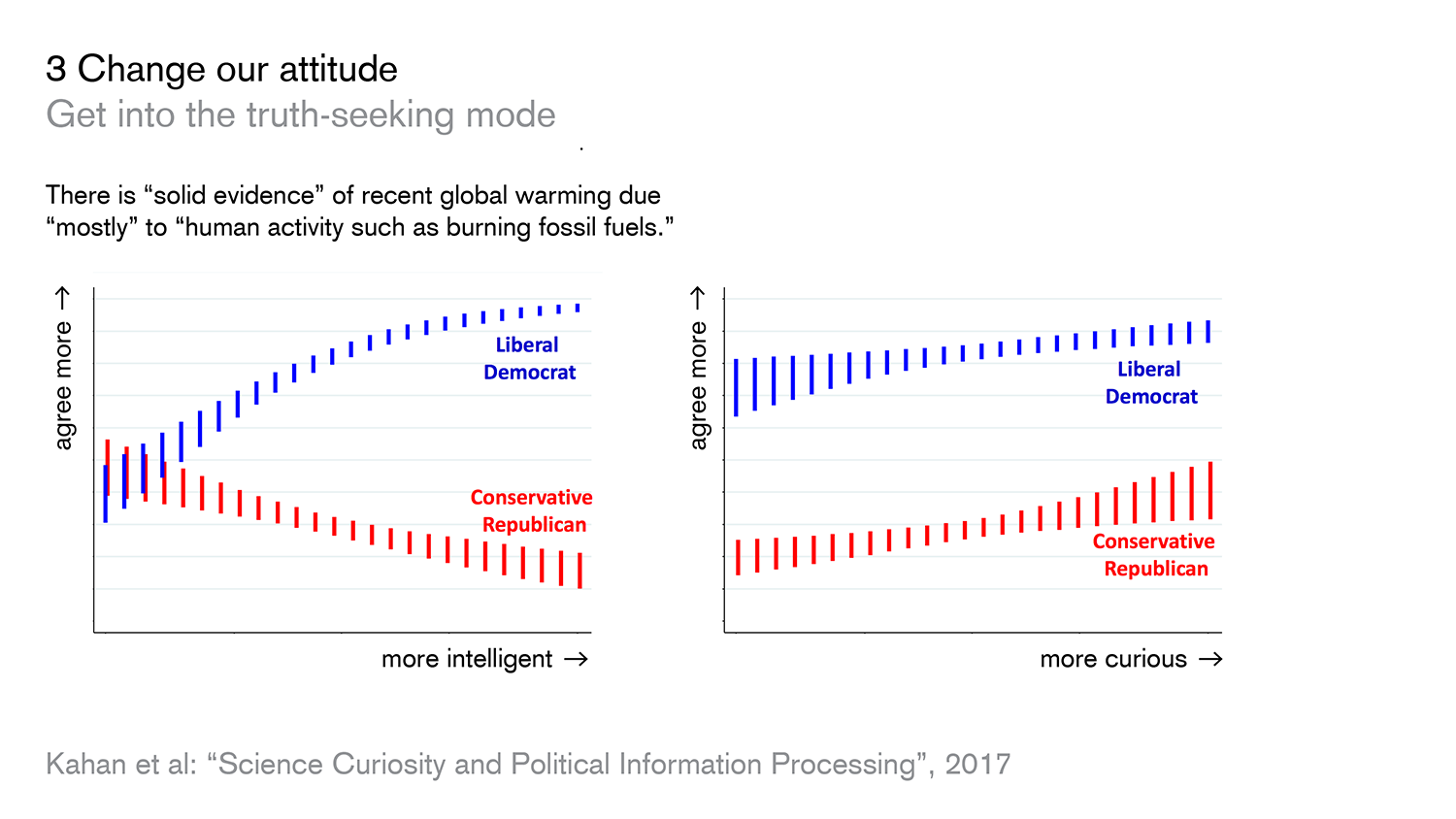

A great idea to realize this attitude is to get people in a truth-seeking mode. The excellent paper “Science Curiosity and Political Information Processing” by Kahan et al states that “individuals can use their reason for two ends—to form beliefs that evince who they are, and to form beliefs that are consistent with the best available scientific evidence.”

The paper shows that people who are more intelligent are more likely to have extreme beliefs (true and false), which seems to be bad news. But it also shows that people who are more curious and driven by scientific thinking tend to believe more true things:

So we should make people more curious! Quizzes and games are a great way to do so, and of course, I need to mention “You Draw It” from the New York Times Graphics team here. What a great coincidence that I wrote about curiosity in a blog post last month, where I explained the beauty of this very graphic.

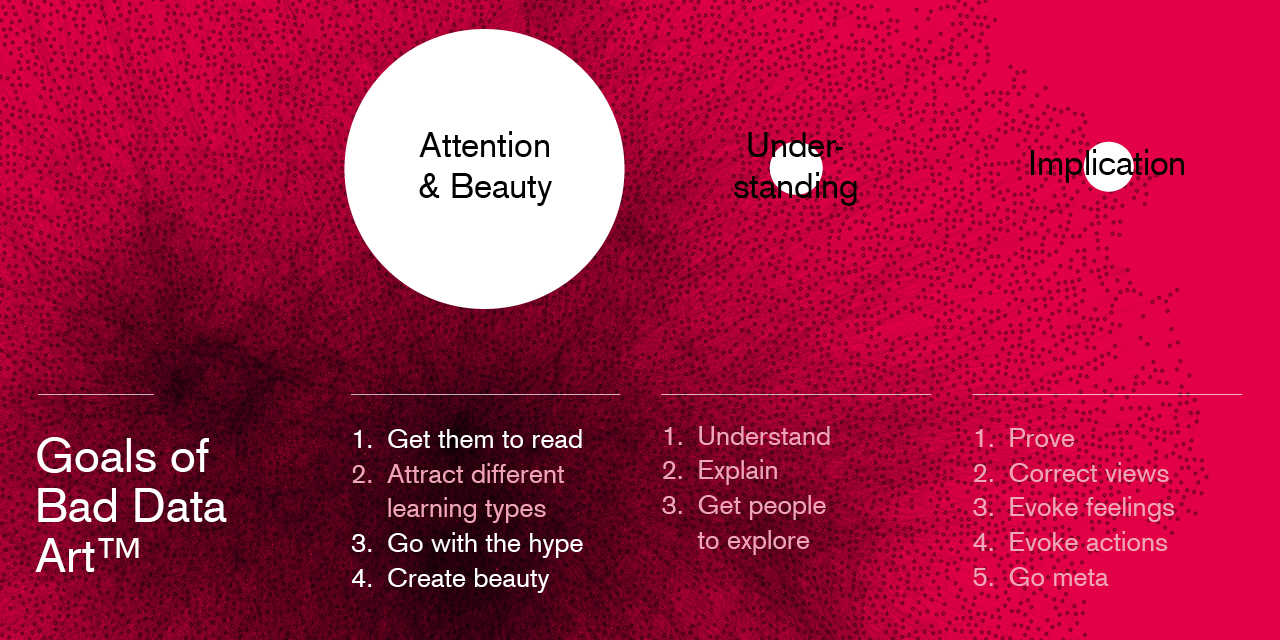

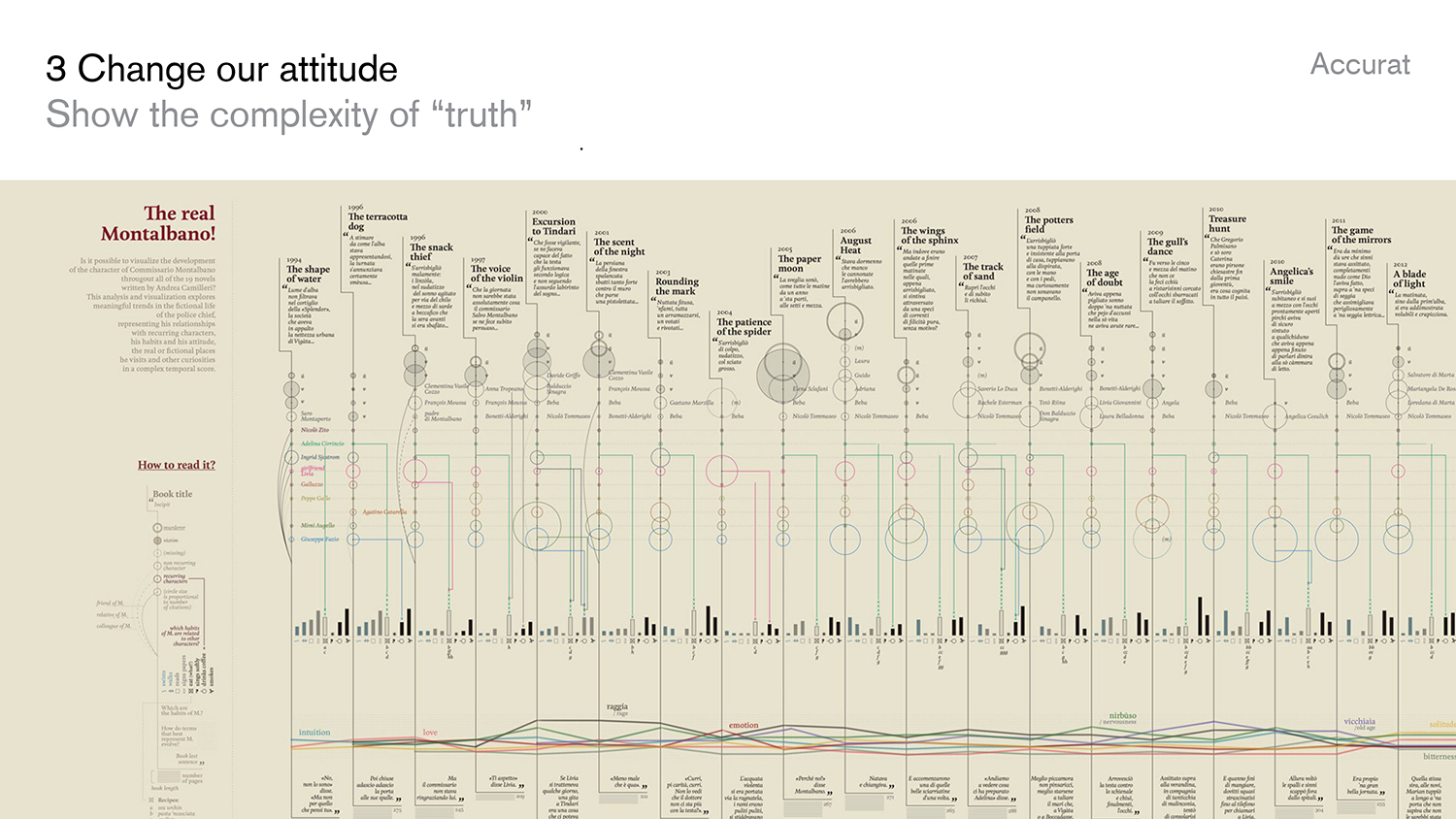

I can also think of three more “changes in attitude” that are closely related to data vis: Showing complexity (including uncertainty), and planting doubt. The latter means explaining that the world is not as simply measured as we sometimes assume it is.

But let’s focus on showing complexity. I would assume that most data visualizations out there are bar charts. Which brings two problems with it: First, every kind of data looks the same; and second, it simplifies extremely.

And hey, that’s good. Simplifying is our job, among many things. But more and more often I appreciate approaches like the one from Accurat, who shows the complexity of the data out there better than any bar charts. The form gives a more honest view of the world. Our beliefs are already simplified enough: Forms that remind us that the facts are not that simple could become more and more important.

The last approach to believe more true things is to remind ourselves of our skin in the game. Having skin in the game means to be directly influenced by the outcomes of something; in this case our beliefs. We have skin in the game when we think that it doesn’t rain, but it does – because we’ll get wet. We get immediate feedback.

But we don’t have skin in the game with most tribe-defining beliefs like climate change, pizza gate, voter fraud. We are not affected by the outcome:

Remember that awesome “Science Curiosity and Political Information Processing”-paper? It states that “Farmers … have been observed to use information on climate change to form identity-congruent beliefs when they are behaving as citizens but to form truth-convergent ones when they are engaging in the task of farming, where they have an end—succeeding as farmers—that can be satisfied only with that form of information processing”. Which basically means: When you ask a Republican farmer if he believes in climate change, he will probably say no – until this belief gets important for his goals to be a better farmer. Reminding ourselves and others of the skin in the game and the personal ways they can benefit from information will make them listen.

D. What does it all mean?

Wow, you’ve made it! That was one long article. Here are all the points we’ve encountered while you were reading this article; and believe me, each category could be filled with far more reasons, causes, and examples:

But what should we do now, after having all this information? Is it a good option to not believe in anything anymore?

I’d say no. I disagree with people who say we need to build beliefs carefully. Beliefs are important for acting in this world – and I’d rather want that we act than not act. In my opinion, we should have grand beliefs. But these beliefs show be flexible like a gummy bear:

Strong opinions, loosely held. That’s a phrase I really like and that I’d like to apply to beliefs as well: Strong beliefs, loosely held. We want big beliefs to act. But when we encounter new facts, we want them to update easily.

Thank you! If you have thoughts, new categorizations and critique, please email me: (lisacharlotterost@gmail.com) or look me up me on Twitter (@lisacrost).