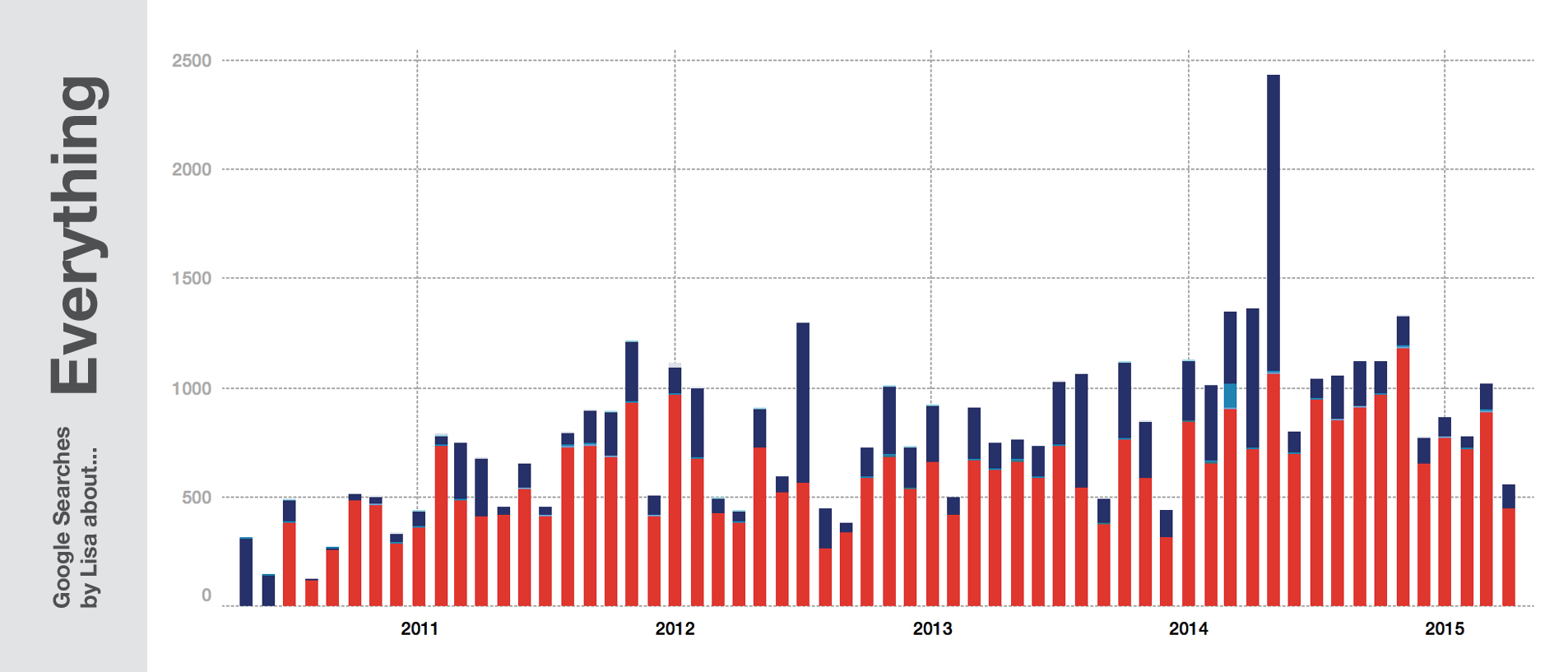

One month ago, I posted an article with an analysis of my Google search history. People liked it. But people also asked “How did you do this?”

It’s easy!

And to demonstrate that, I will write my first tutorial. It’s an extremly detailed tutorial for absolute beginners in …well, everything. If you can code, there are better ways for you do clean up and visualize the data (eg., a way to merge the Google Search history JSONs was written down here in Ruby by Daniel Kirsch). And if can’t code, but you’ve dealt with JSONs and/or Google Refine before: this is the short version – or, let’s say, ONE short version, because of course there are many ways to visualize the data:

- Download your archive here and unzip it.

- Merge the JSONs.

- Convert the JSONs to a TSV or Excel file (eg with Google Refine).

- Convert the timestamps in Excel/Libre Office with the following formula:

=LEFT(A1;10)/(60*60*24)+"1/1/1970" - visualize and analyse your data with Tableau Public.

Here comes the long version:

1. Download your archive

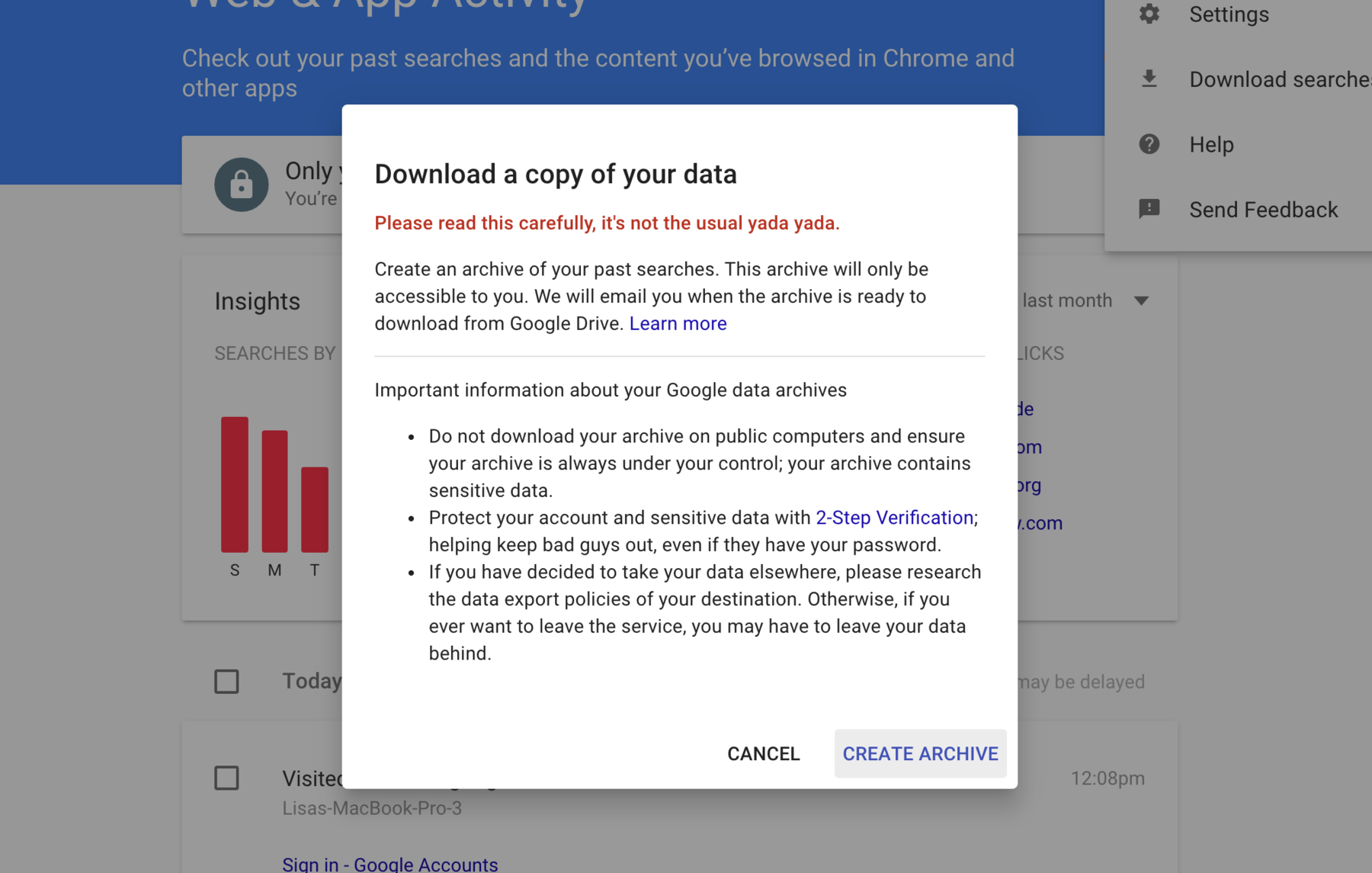

Follow the instructions on this site and you end up getting such a screen:

Listen to the Google guys: Be careful with your data! It IS sensitive. It contains your darkest desire and highest hopes – especially if you’re as careful with what you type in Google as 99% of the population.

After clicking on “Create Archive”, you’ll need to wait. Google will send you an email as soon as your archive is ready. Then download this archive and unzip the ZIP file they give you. Congratulations, you know own your Google Search History (together with Google. Well, Google owns it more.) First step: Done!

2. Merge the JSONs

You unzipped your files? Good! Looks like it’s not a simple Excel file called “YourSearchHistory.xls”, right? The files you unzipped are JSONs, a neat file format. Google created one JSON for each quarter in which you’ve used Google Search. Which might be convenient for them, but not for us: We want to have ONE file for ALL our search queries. So we need to merge our JSONs to one mega JSON. And the least advanced but most simple way to do that is by hand.

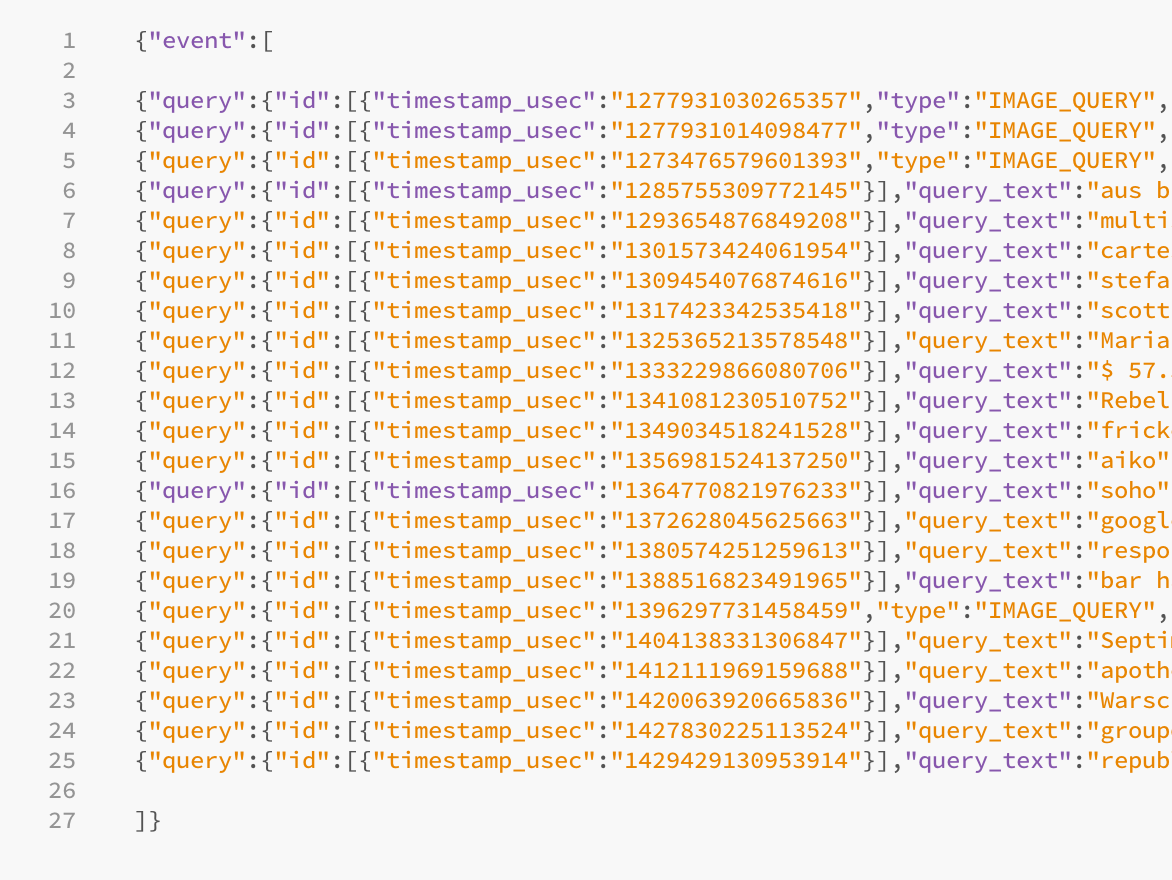

Try to doubleclick on such a JSON file. If you’re not satisfied with the software that opens this file, you might want to download an editor like Sublime or Brackets. Your JSONs folder and your open JSON files should look like that:

So what do we see? Let’s understand the structure and content of our JSONs a little bit, so that we’re merging them correctly.

Every JSON starts with an{"event": [. And because every bracket that got open in JSON needs to be closed at some point, every file ends with ]}.

Between these two brackets go all our queries. All of them come with a unix timestamp that humans can’t really read, but that work perfectly for computers. We’ll convert them later in the process.

Then we can see two objects called “type” and “tbm”. They basically communicate us the same: Which kind of search we have used. “isch” means image search, “blg” means blog search, “nws” means news search, etc. Find all values on this site.

And at the end, we can see our search query text! In this case, I’ve searched for images about “intellectual property” at the 4th of July 2010 at 3:53pm.

{

"query": {

"id": [

{

"timestamp_usec": "1278251637054301",

"type": "IMAGE_QUERY",

"tbm": "isch"

}

],

"query_text": "intellectual property"

}

}

When we’re now merging our JSONs, we can’t just copy and paste one JSON to the other. We need to make sure that we maintain the struchture: we open only once with {"event": [ and we’re only closing once with ]}. Meaning, we need to delete all the additional {"event": [’s and ]}’s before we’re copy and pasting them. So our final JSON should look like that:

There is another thing you need to change in your JSON: commas. Before the last closing brackets of the whole final JSON, there shouldn’t be a comma. But between all the other {"queries"}, there needs to be a comma:

{"event":[

{"query": “…”},

{"query": “…”},

{"query": “…”}

]}

To sum up the rules for merging our JSONs by hand:

- Delete all the opening

{"event":[and closing]}of all JSON files. - Put a comma at the end of each JSON file except the last one.

- Copy and paste all JSONs into one file.

- Add a beginning

{"event":[and a closing]}.

YOU DID IT! Yeah! To get that right is the hardest part of the whole tutorial – everything will be easy from now on.

3. Convert the JSONs to an Excel file

JSONs can be directly visualied with d3.js for example – but you don’t know Javascript. So we will need to convert this file to a format that Tableau Public can read (=the software we’ll use to visualize the data). For the converting part, we’ll use OpenRefine, actually a tool to clean up messy data. There are many JSON-to-CSV/TSV-converter online, and if your JSON is fairly small, I would recommend them. But because my final merged JSON file “AllSearches.JSON” was 4.6MB big, these tools had some difficulties dealing with it. OpenRefine, however, did a smooth job. Also: I’m a huge fan of this software. So go download it here and use it to clean up data on every future occasion!

For our little project, we will click on exactly four buttons. So open OpenRefine (it should open in your browser) and do the following:

- Below “Locate one or more files on your computer to upload” in the “This computer” tab, choose your JSON file and click “Next”.

- It should now say: “Click on the first JSON { } node corresponding to the first record to load.” Go ahead and click on the first

{"query":...}object after your opening{"event":[.

- You should see a table with your content! Finally! A table! Something we KNOW! Awesome. Let’s export that delicious table. Click on “Create Project” in the upper right.

- You should see 10 or so rows of your table again. Click on “Export” in the upper right and choose “Excel”.

- Done! You may close OpenRefine now. Or you can stay and admire it a little bit more.

4. Convert the timestamps

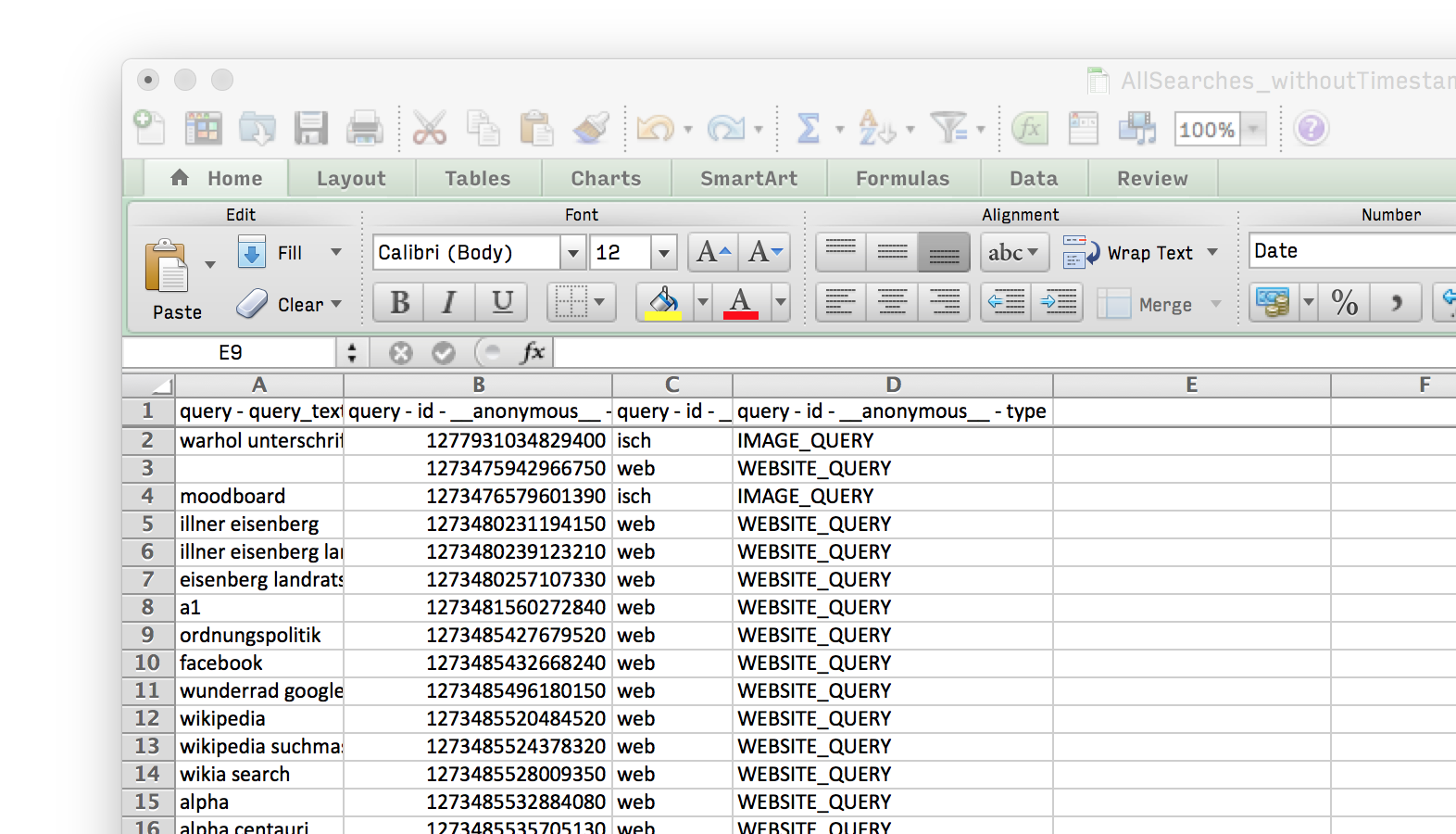

Open the exported Excel file with Excel or LibreOffice. You should see lots and lots of rows and four columns:

The first one shows your query text. The second one your timestamp. The third one your query tbm and the fourth one your tbm written as type. You will see that I didn’t lie to you: “tbm” and “type” ARE communicating the same. So if you want to, you can delete one of the columns.

You may wonder: “Well, we got our Excel file, right? Tableau can read Excel, so why are we not in Tableau yet?” Patience you must have my young padawan. Look at the long number in your second column with the header “query - id - anonymous - timestamp_usec”. Can you read it? No. Neither can Tableau.

So we opened up Excel to convert that timestamp to a date that we and Tableau can read. Do the following steps:

- Insert a new column right next to our timestamp colum. For that, select the third column and click “Insert” in the “HOME” tab.

- Copy and paste the following formula in the cell right to the first timestamp:

=LEFT(B2;10)/(60*60*24)+"1/1/1970". I assume that your first timestamp cell isB2. If not, adapt the formula! Also, check the language settings. If you’re in a German Excel, for example, your formula is=LINKS(B2,10)/(60*60*24)+"1/1/1970". - Apply that formula to ALL cells in your new third colum right to the timestamp colum. How? Select the first cell with your formula, then hover over the bottom right corner of it. A fat black “+” should appear. Double-click on it and see magic happen!

- You don’t see a date yet? Select the whole column and choose “Date” instead of “Genereal” or “Number” in the drop-down menu of the “HOME”-tab.

- Give your new column a name, like “DateYeahFinallyOhManThatsAwesome”. And don’t forget to save your Excel sheet!

If you don’t just want to follow instructions but also want to know “Why?”, you might be curious about the formula =LEFT(B2;10)/(60*60*24)+"1/1/1970". What does it do, exactly?

For that, you need to know a little bit about Unix time. It’s the attempt to display time as a simple machine-readable number instead of having these inconsistent date formats like “01/07/2015 16.50” or “2015/07/01 4:50pm”. The unix time increases with every second. And it has counted all seconds since the nice winter day of 1st of January 1970. And, last thing you need to know: The unix time has 10 characters.

Now look at our timestamp column: Whoooah, every cell has more than ten characters! What does it MEAN? It just means that Google wants to be damn exact and gives us the microseconds, too. But no problem! We just cut down the microseconds; seconds should be enough for us.

So that’s what our formula is doing: First, it only takes the first ten characters of our timestamp cell B2 and ignores the rest of it: =LEFT(B2;10). Then, it divides these numbers through 60 seconds, 60 minutes and 24 hours: =LEFT(B2;10)/(60*60*24). And then it adds the date on which the unix time started counting: =LEFT(B2;10)/(60*60*24)+"1/1/1970". And voilà! A “normal” date is born.

5. visualize and analyse your data with Tableau

Finally! We arrived at the part of this tutorial in which we will see a visualization of our data. For that, we’re using Tableau Public. Why that, you wonder, and not Excel? Because Tableau Public is really good in dealing with fairly huge numbers, having an intuitve interface and therefore letting you see different perspectives of your data in quick and easy way. Try it. You will like it. If you haven’t downloaded it yet, go here and do it.

Then, open it and do the following steps:

- Import your Excel sheet (click on “Excel” below “To a file” and locate your file).

- Click on “Go to Worksheet” in the upper left. Voilà, you imported your data!

- Play around with the data! You can drag and drop objects like you want to. Here’s one possibility to see the count of your search queries in years, quarters, months or weeks and sorted in categories:

- You can also search for specific search queries (searching for search, yeah!). Just drag “queries” to the “Filter”-field and then right-click on it to select “Show Quick Filter”. Try to search for places, hobbies, tools, ideas, movies, etc:

The sad thing about Tableau Public? You can’t save your results on your computer, only in the Tableau Cloud. And listen to the Google guys: Your data is extremly sensitive! You might not want to save it to ANY cloud.

That’s it! You’ve made it! Congratulations! You downloaded, merged, cleaned, visualized and analysed your Google Search history. I’d love to see what you’re coming up with. If you have some interesting insights or visualizations, send me a link at lisacharlotterost@gmail.com or comment on this blog post. Also, if you know a way to analyse your data in a super simple way, please share your knowledge!