This is the transcript of a talk I gave at NACIS 2016 in Colorado Springs. I didn’t include all of the slides, to make it more readable.

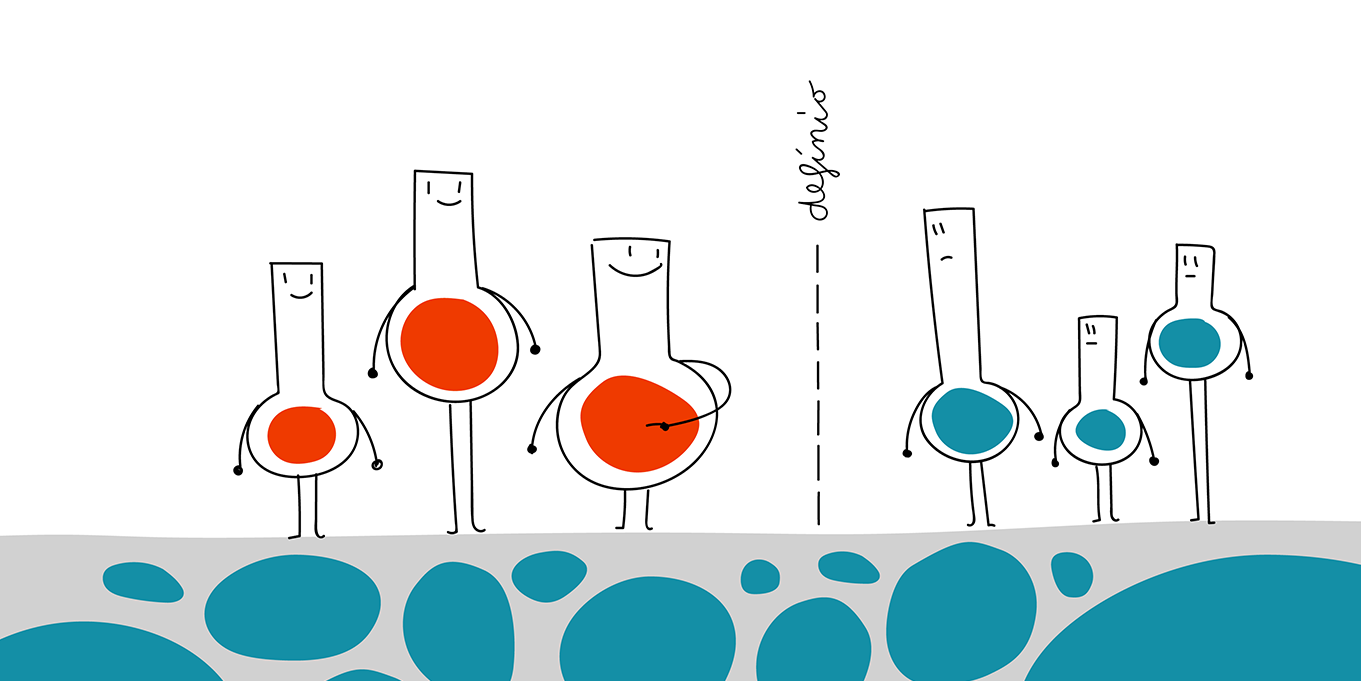

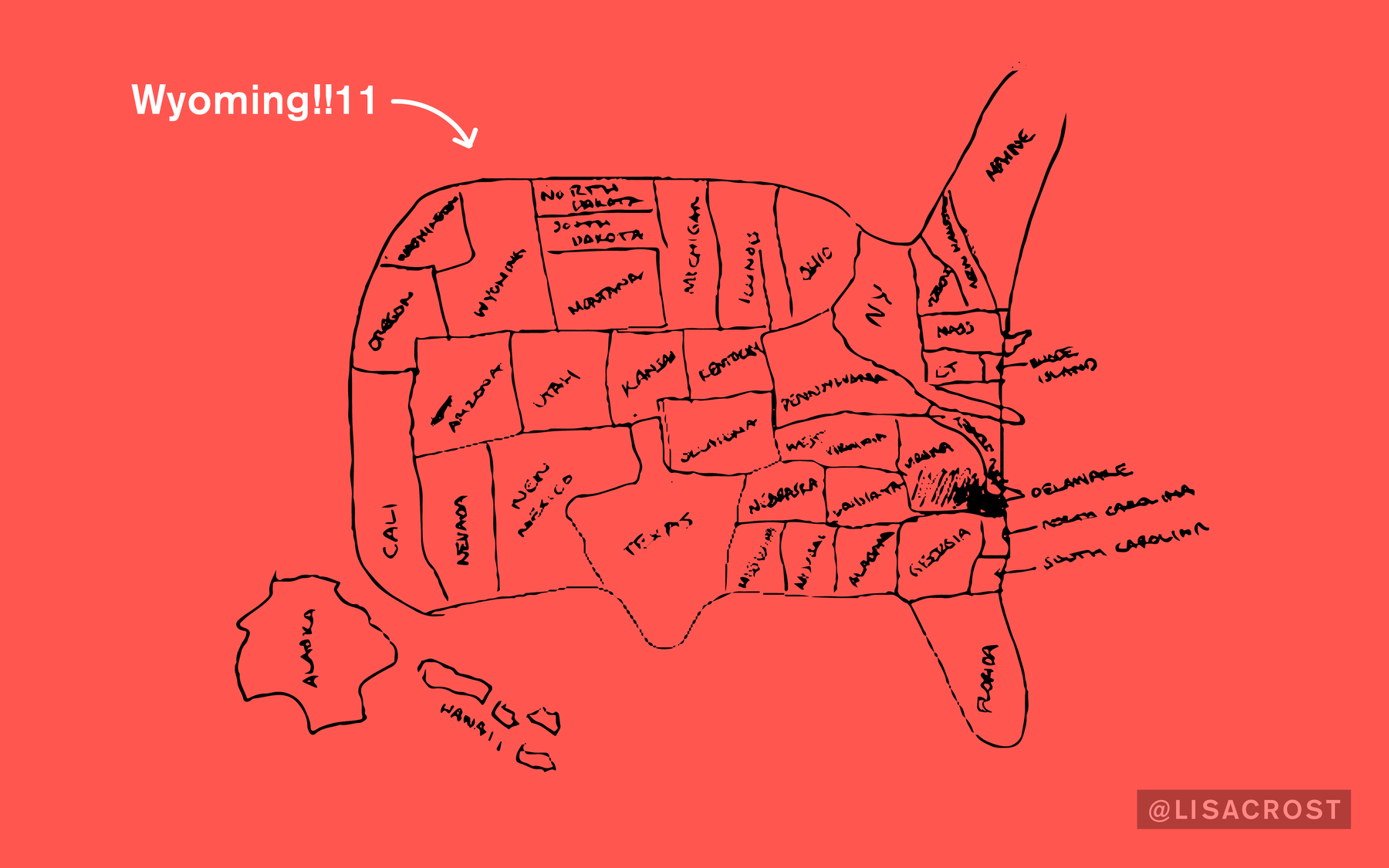

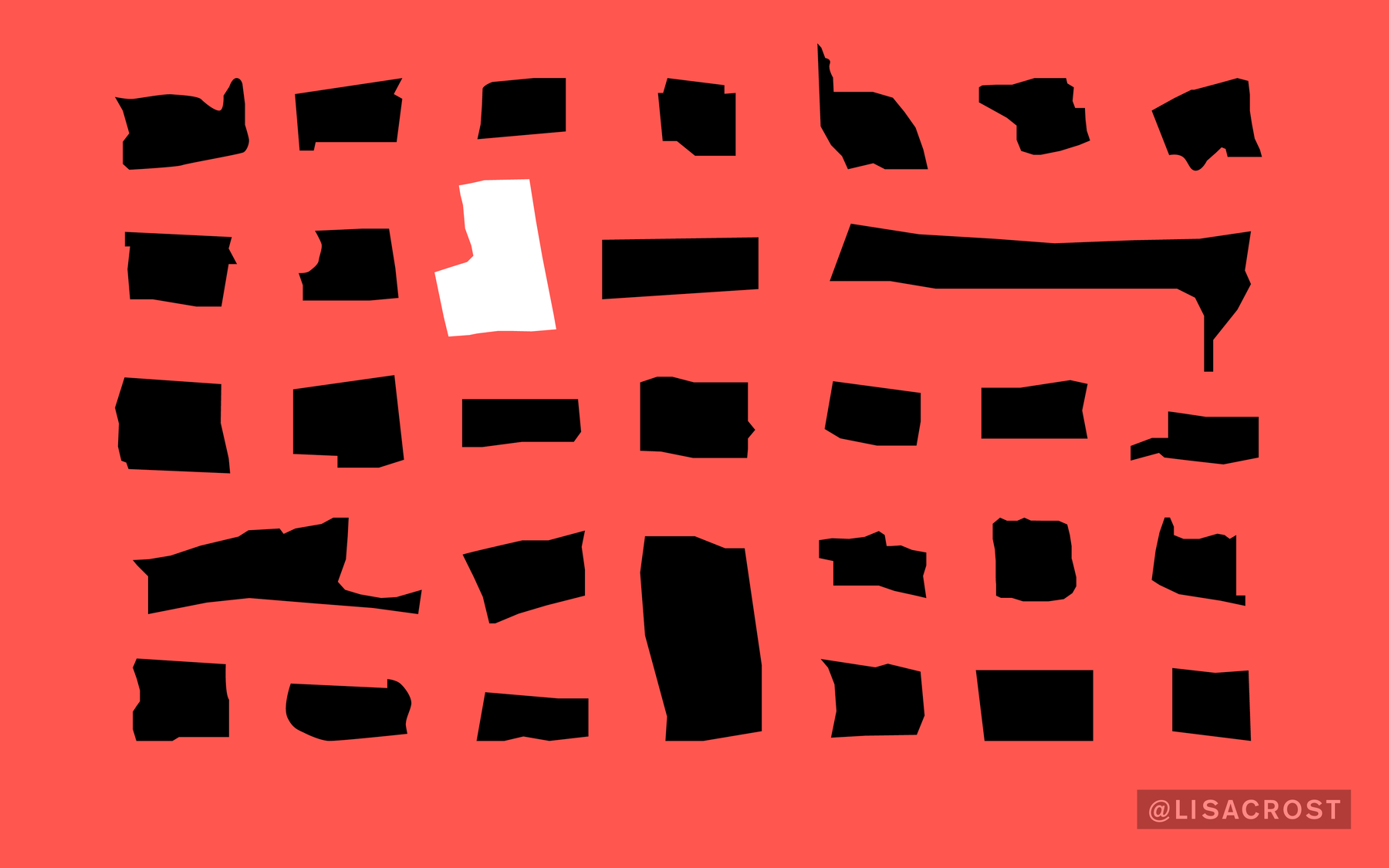

Wyoming is boring. Nobody cares about Wyoming. I don’t know that because I asked people or because I was there, but because I looked at the maps that people drew of the United States. I found 48 of these maps, and 17 people forgot to draw Wyoming in the first place. (Nobody forgot California or Florida.) Well, this person included Wyoming:

Here we can see the shapes of all the drawn Wyoming’s. A few people remember that Wyoming looks like a simple rectangle. Most of them don’t:

Hey, my name is Lisa and when I don’t enjoy NACIS, I visualize data. But today I want to talk about Map Poetry: Why we need it, what it is and how it can change the way we see the world.

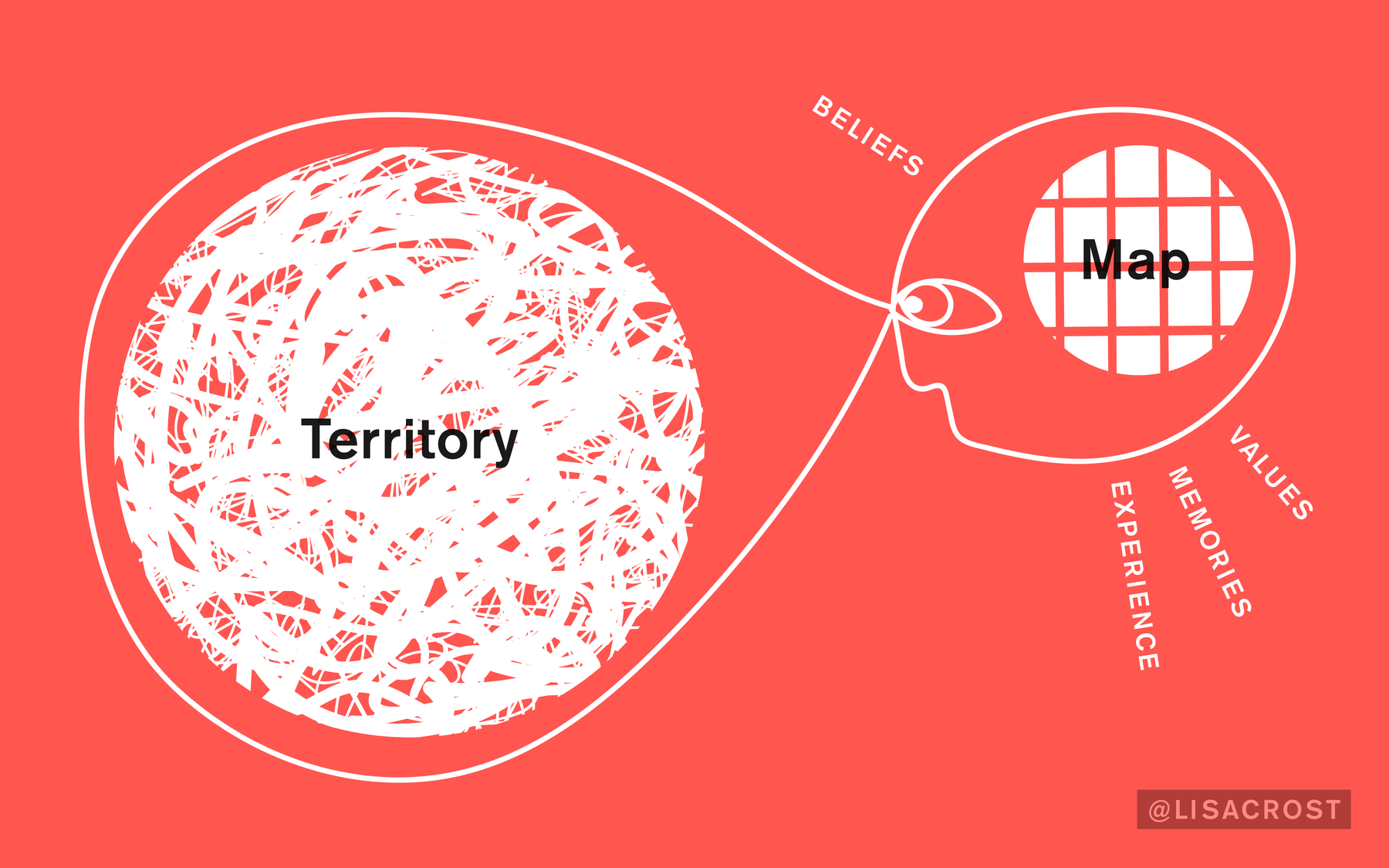

When we look at a map of the world, we can’t see it as it is. We all lay an internal map of the world on top of the geographical one and only see what’s important to us. This internal map consists of memories & experience, associations, values, beliefs. It is incredible individual. There is no internal map that matches a second one. We all look at the same world differently. And we all look at the same maps differently, and sees different things; according to our internal map of the world.

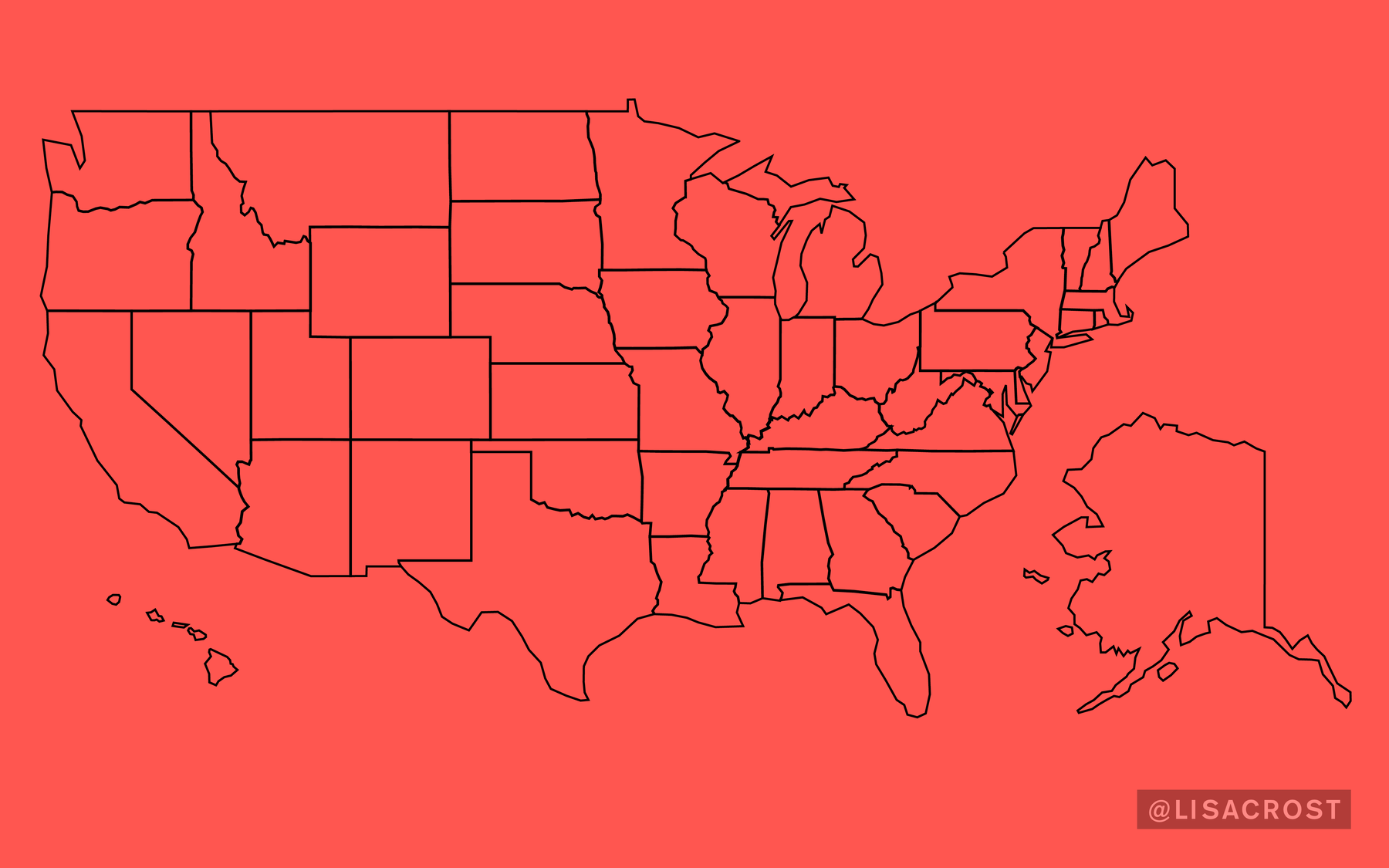

What do you see here? Where do your eyes get drawn to? Where you live? Where you grew up? Or, when you’re not from the US, the places that Hollywood told you are important?

Hand-drawn maps can show us what people actually notice in their environments. For some of you, Wymoning might be incredible important, because of beautiful memories (or terrible memories). And then of course you’d know that Wyoming is of rectangular shape, because that’s the place you notice when you look at a map of the US. Most people don’t notice Wyoming when they look at the same map. For most people, Wyoming is not important.

For me, Berlin is important. I lived in that city for 2 years. This is a map of Berlin as we all see it on OpenStreetMap:

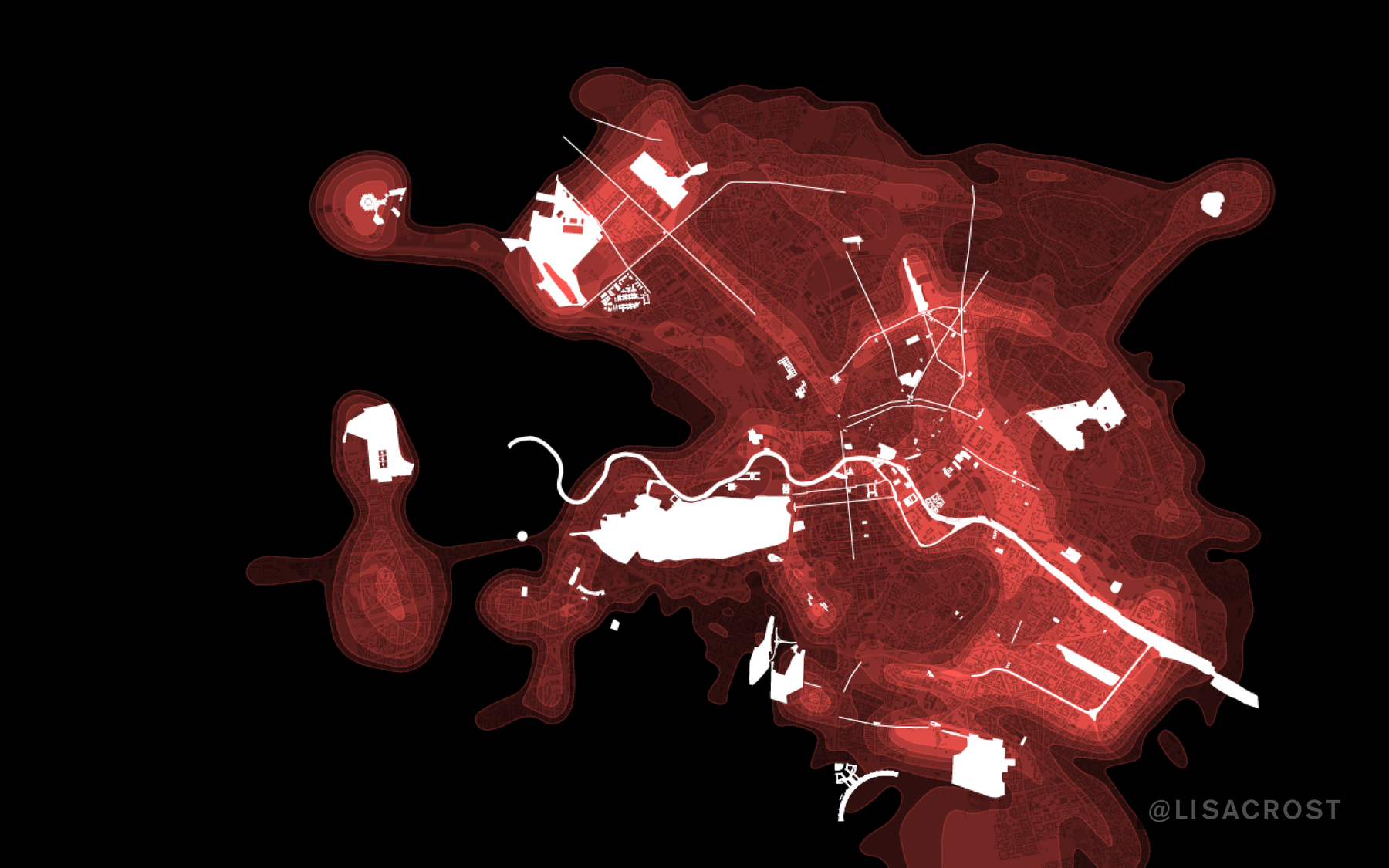

This is a map of Berlin how I see it. The brighter an area, the more comfortable I feel navigating. The white buildings and streets are the places I know by name. This is my internal Berlin map:

If somebody asks me: “Have you heard of that new restaurant x? It’s between “Do you read me?” and Rosenthalerplatz on the Kleine Augustusstraße”, then I think: Aaah, great, I know exactly where that is. Well, ok, that’s not how it works, most often. Most often somebody asks me: “Do you know street a? In district b?” and I say: “No, is that close to shop c?” Then they say “Nah, it’s close to park d…do you know this one?” And it takes some time until we find streets and locations that are in the internal maps of both of us.

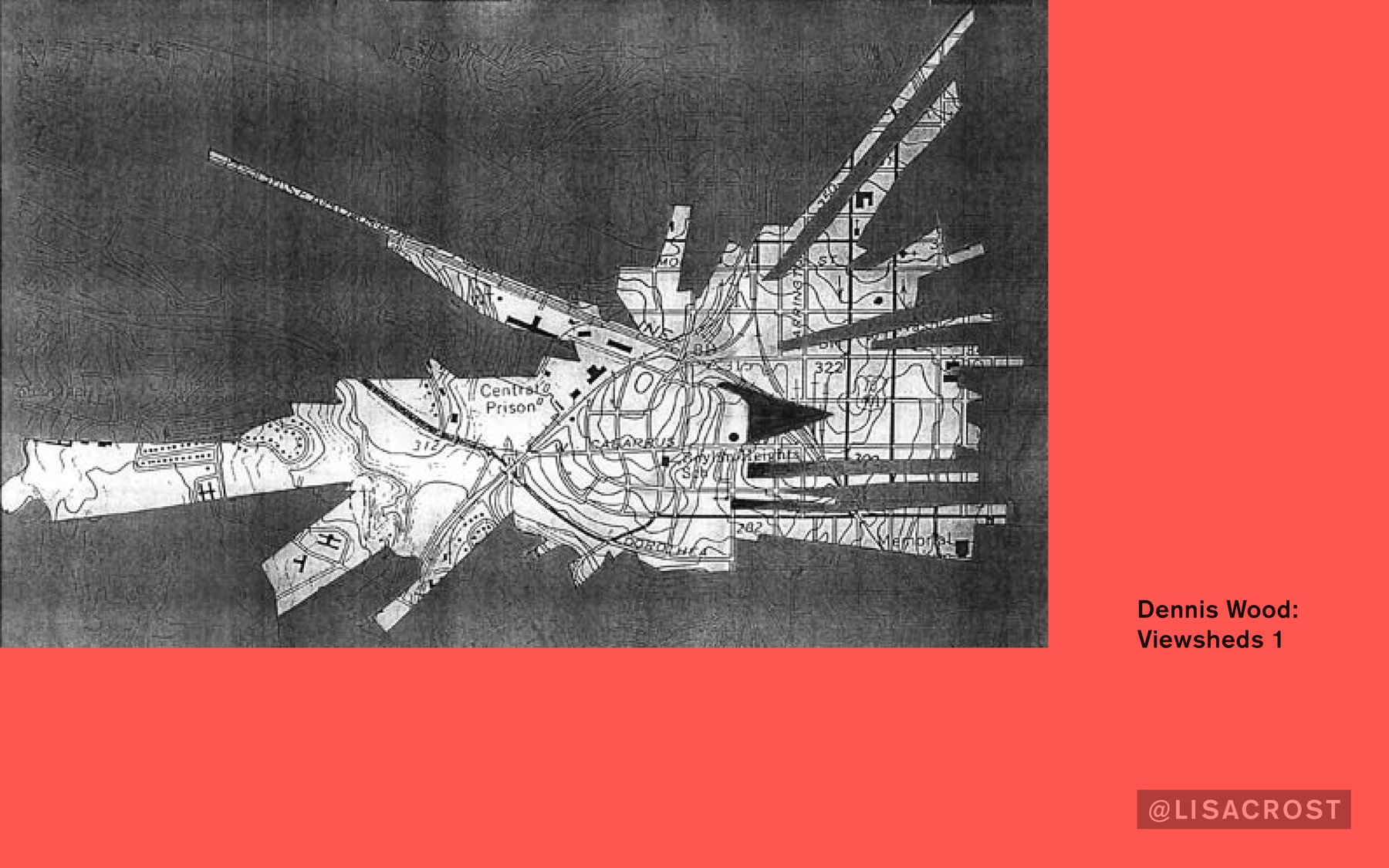

Here is a map of Dennis Wood that has a similar idea: It’s also cutting away things that he can’t see.

But in contrast to my internal Berlin map, we all share that view, because it’s an actual view. It’s not an internal map. He actually stood on a hill in his neighborhood and drew away parts of the map that were not in his view field. I like that map a lot, because it’s so paradoxical: Maps were supposed to give us an absolute overview. And he takes the maps and says: “What I can’t see from here, nobody should be allowed to see on the map. There is no world beyond my perception of it.” And that’s true for internal maps as well: For our internal maps, what we can recall, exists. What we don’t remember doesn’t exist. We cut away huge chunks of the territory to build our internal maps.

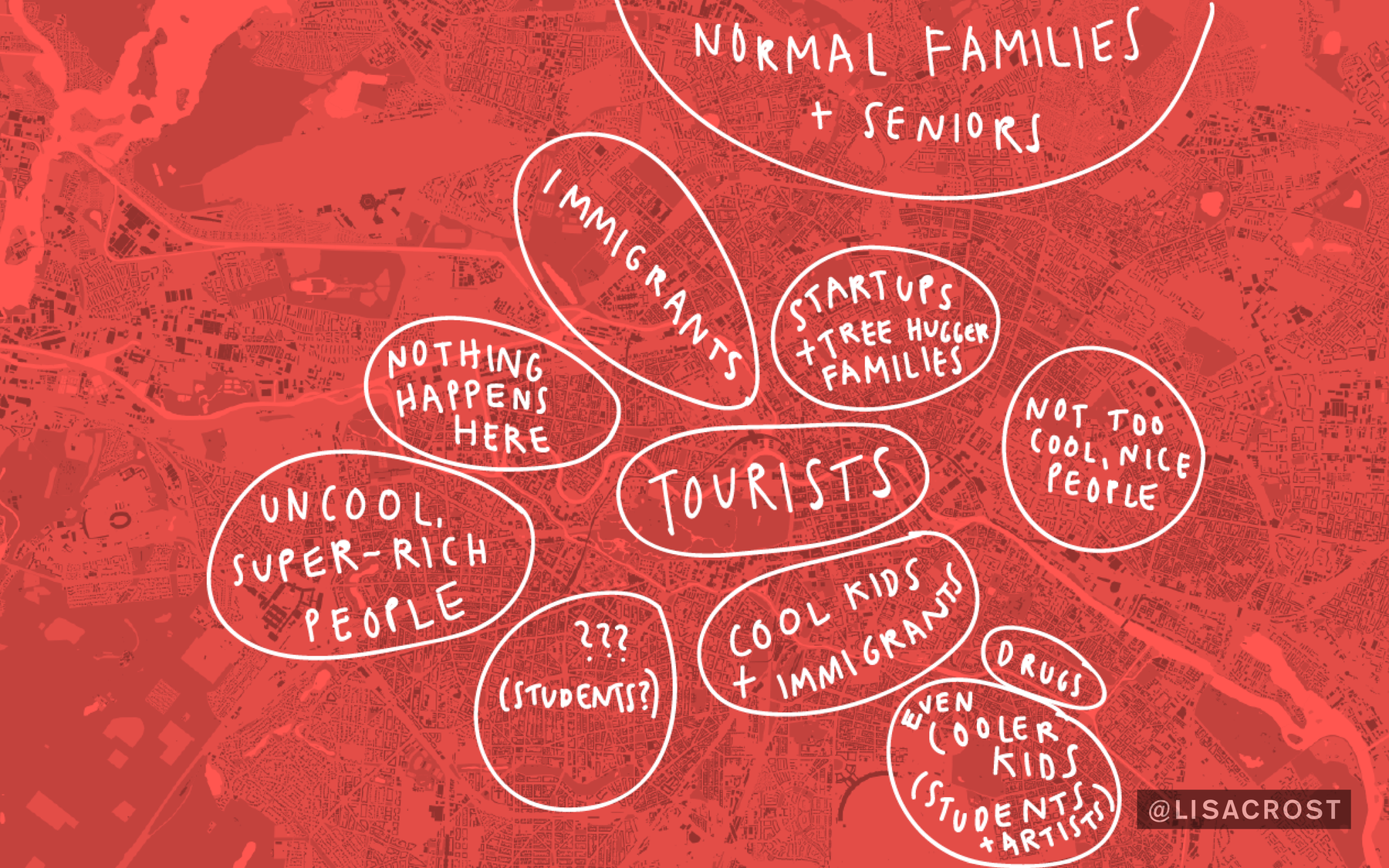

An internal map that many of us share are stereotype maps. Many Berlin people can agree that this is how Berlin works. It seems to add a layer of meaning to the city. But what it really does is cutting away SO, SO much of the meaning. It’s a map that simplifies extremely.

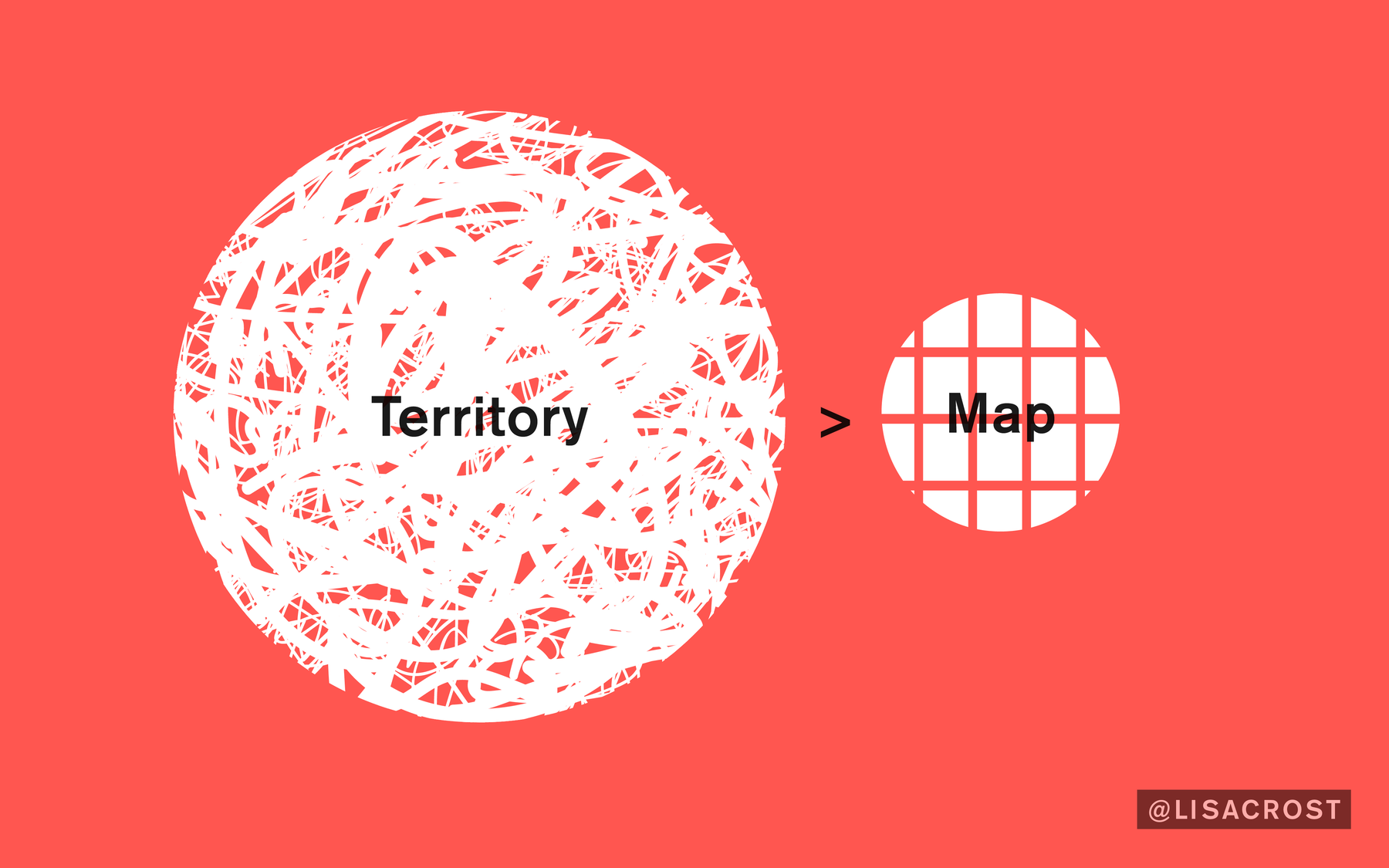

Of course, each map simplifies. That’s what maps are made for. The map can’t be the territory. We can’t deal with the chaos out there. Both the geographical and the internal map must simplify to be useful.

A geographical map, for example, cuts away people. This map of Berlin looks like there don’t live any people. It’s a ghost town. Of course, we understand that simplification. Geographical maps are mostly built for navigation, and we don’t need to know things like the number of people on the street to navigate.

Internal maps have a similar goal: They too are there to make navigating the world possible and efficient. I don’t have the time and motivation to actually poll every single person who lives in these Berlin neighborhoods, so I choose to put them all in one big basket and label it with the stereotype that seems socially accepted.

But with geographical and internal maps, it’s important that we know THAT we simplify. And that we are aware HOW we simplify, and what the limitations are.

Eviatar Zerubavel says: “Examining how we draw lines will […] reveal how we give meaning to our environment as well as to ourselves.” And here’s where Map Poetry gets important. I’d argue that Map Poetry can make us aware of the lines we draw, and can bring back the cut-away junks.

Let’s start with a definition. We all have a mental image of what Maps are in the sense we talk about it here at that conference: They are geographical representations of the world out there.

But what’s Poetry?

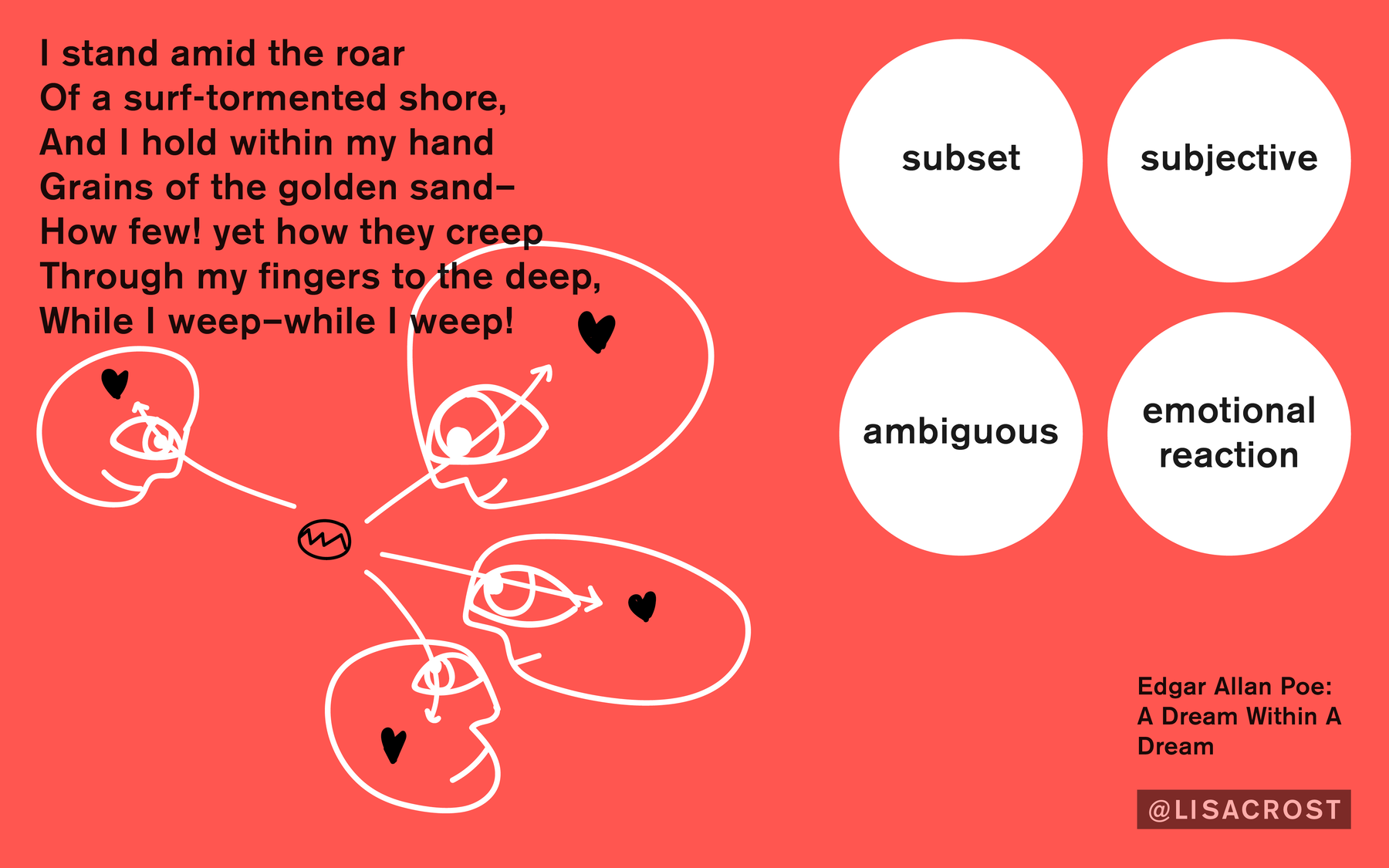

This, for example. It’s an extract from Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Dream Within A Dream”. He talks about a very specific experience: Standing on the shore, holding sand, weeping:

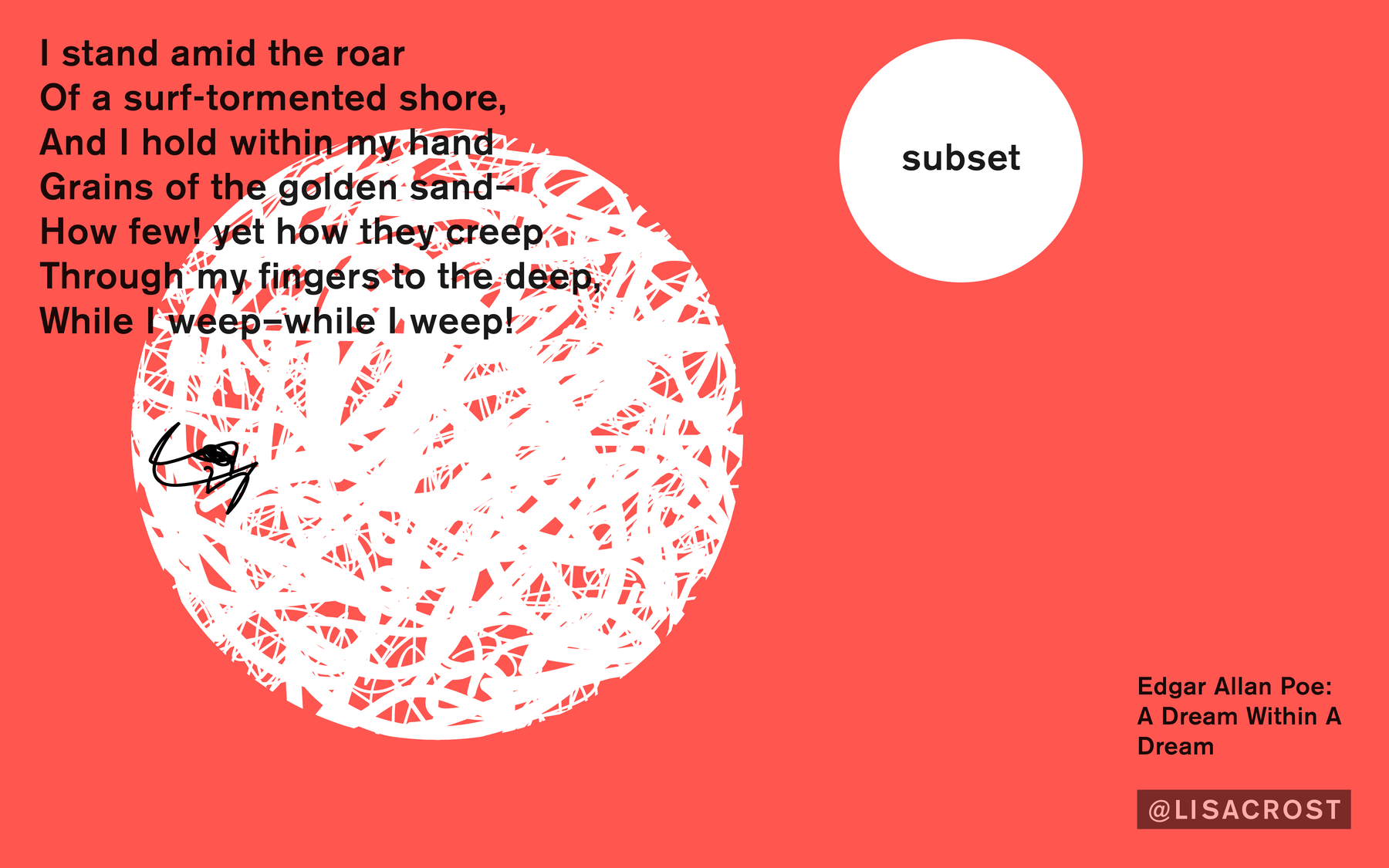

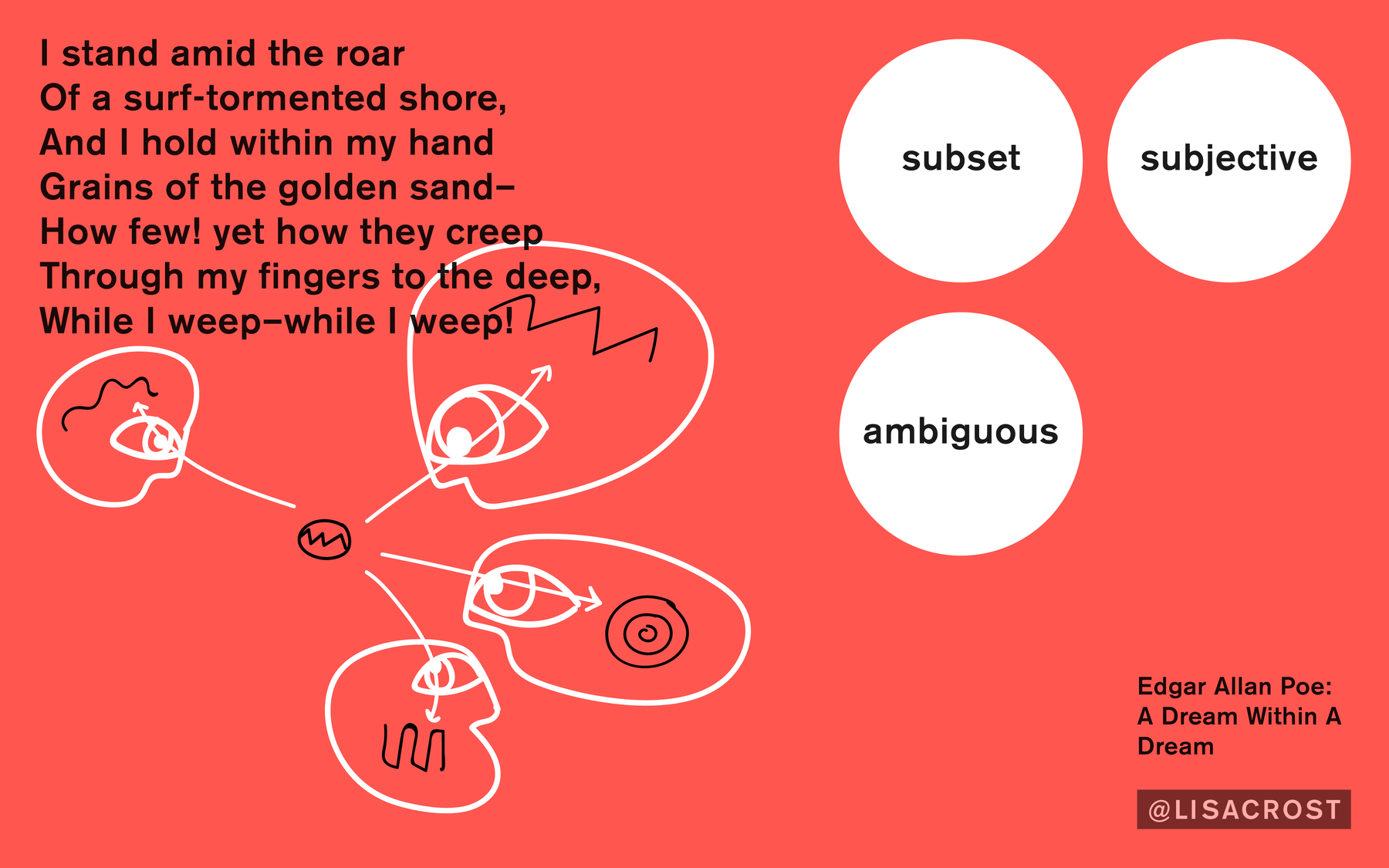

This is the first trait of a poem: Most often, they describe a very small subset of the world – quite in contrast to a map, which tries to give you an overview. Poe describes only a tiny experience in his life.

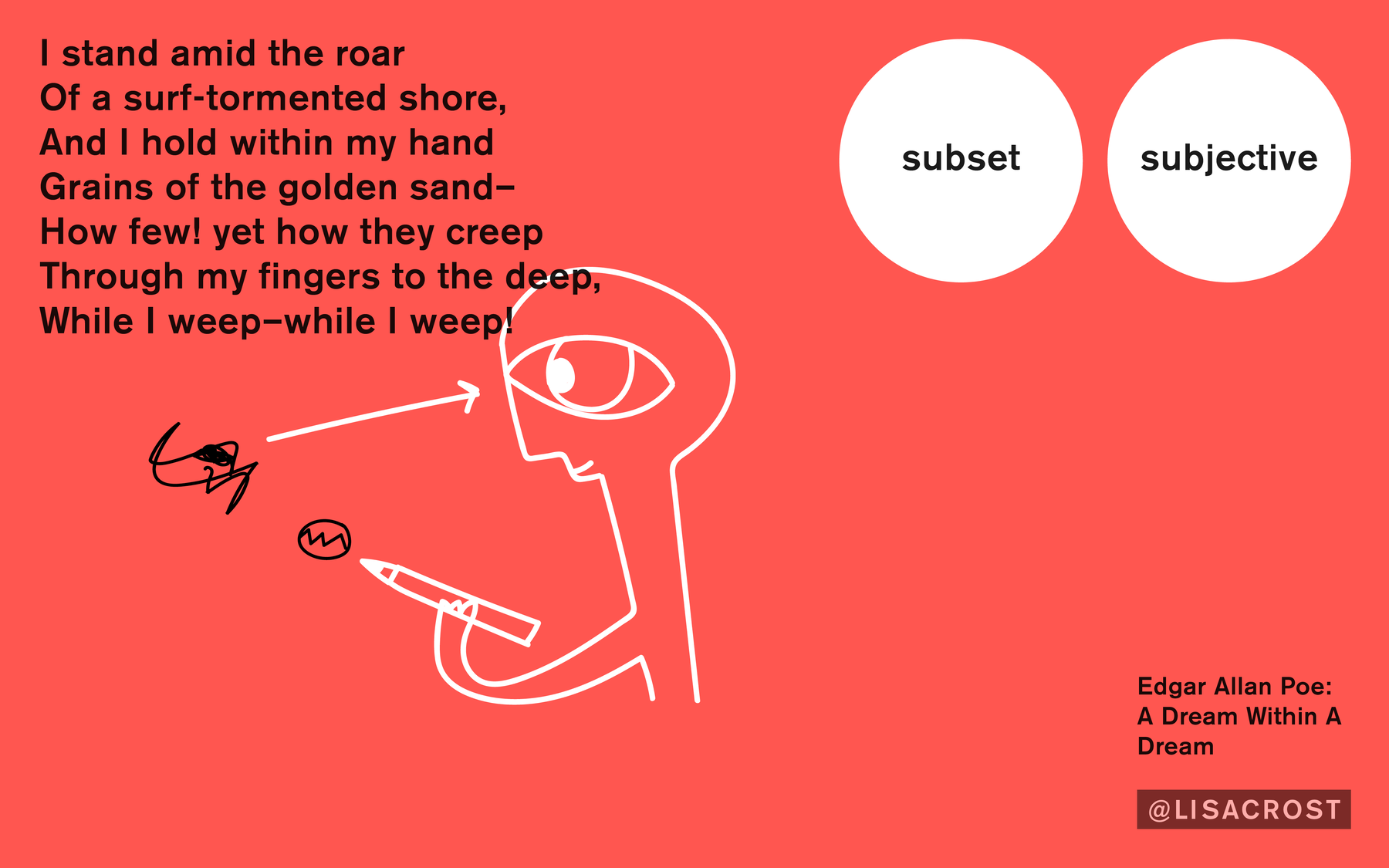

And it’s important to note that it’s a very personal experience he talks about. What he describes is highly subjective (not as objective as most maps try to appear).

A third virtue of poetry is its ambiguity. Poems can be interpreted in hundred different ways. Everybody reads something different out of the it.

And in the best case, poetry doesn’t just result in a rational interpretation, but evokes an emotion in the reader. As a piece of art, a poem is sublime.

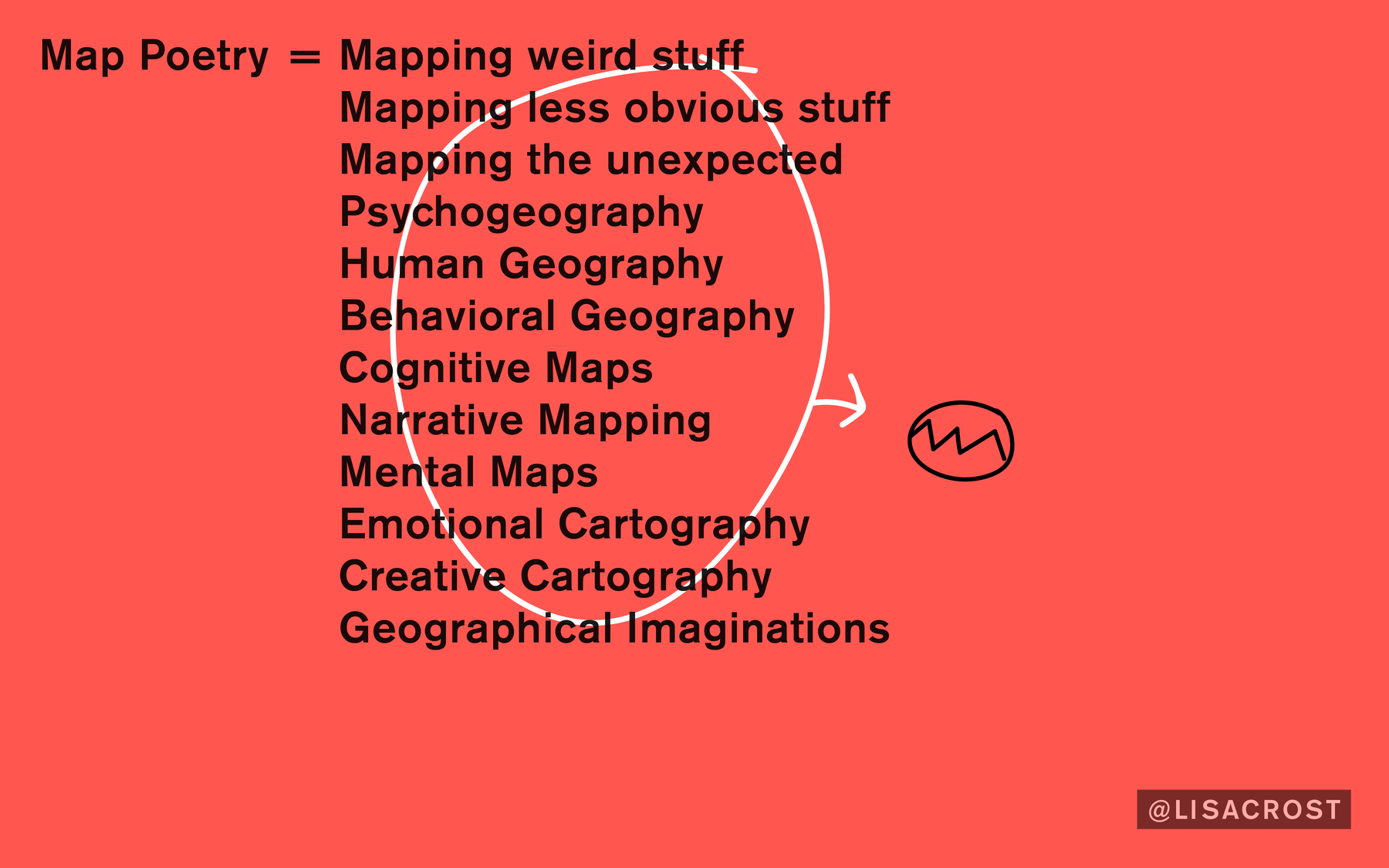

Map Poetry (how I define it) has all these traits, especially the first two ones. Map Poetry doesn’t give us the overview, how maps usually do it. Map Poetry focuses on a subset of the world and looks at it from a subjective standpoint rather than a seemingly objective god-like perspective. Map Poetry makes us aware that the territory out there is, indeed, complicated, and complex and entangled. And that we all perceive it differently.

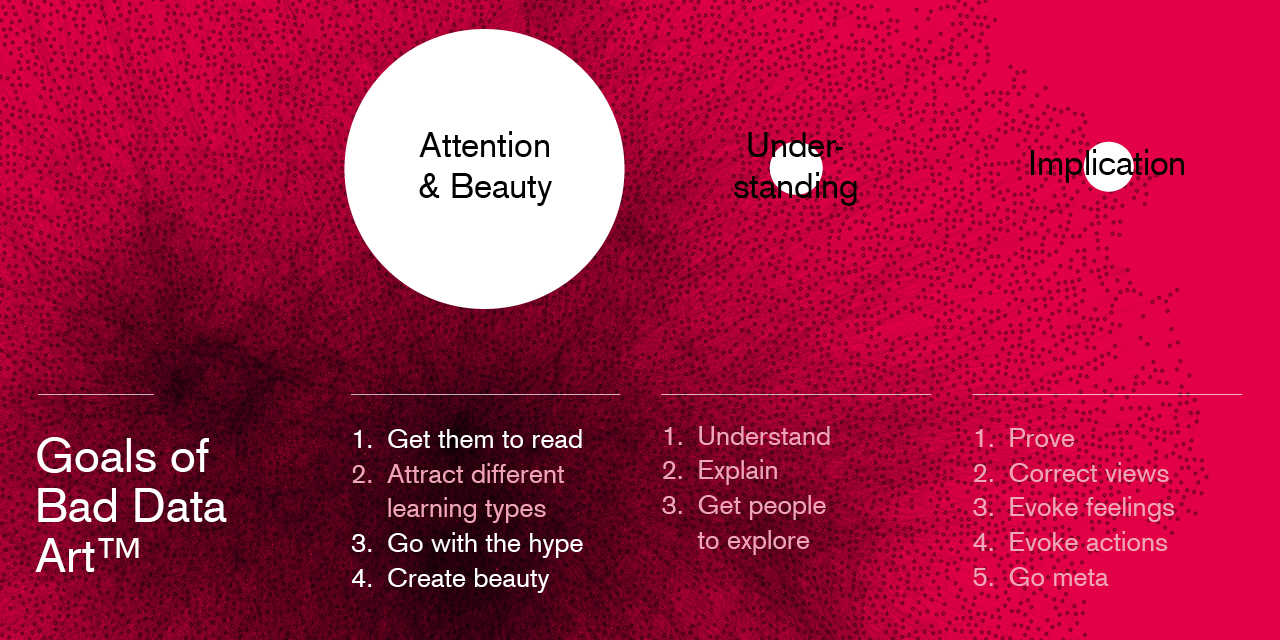

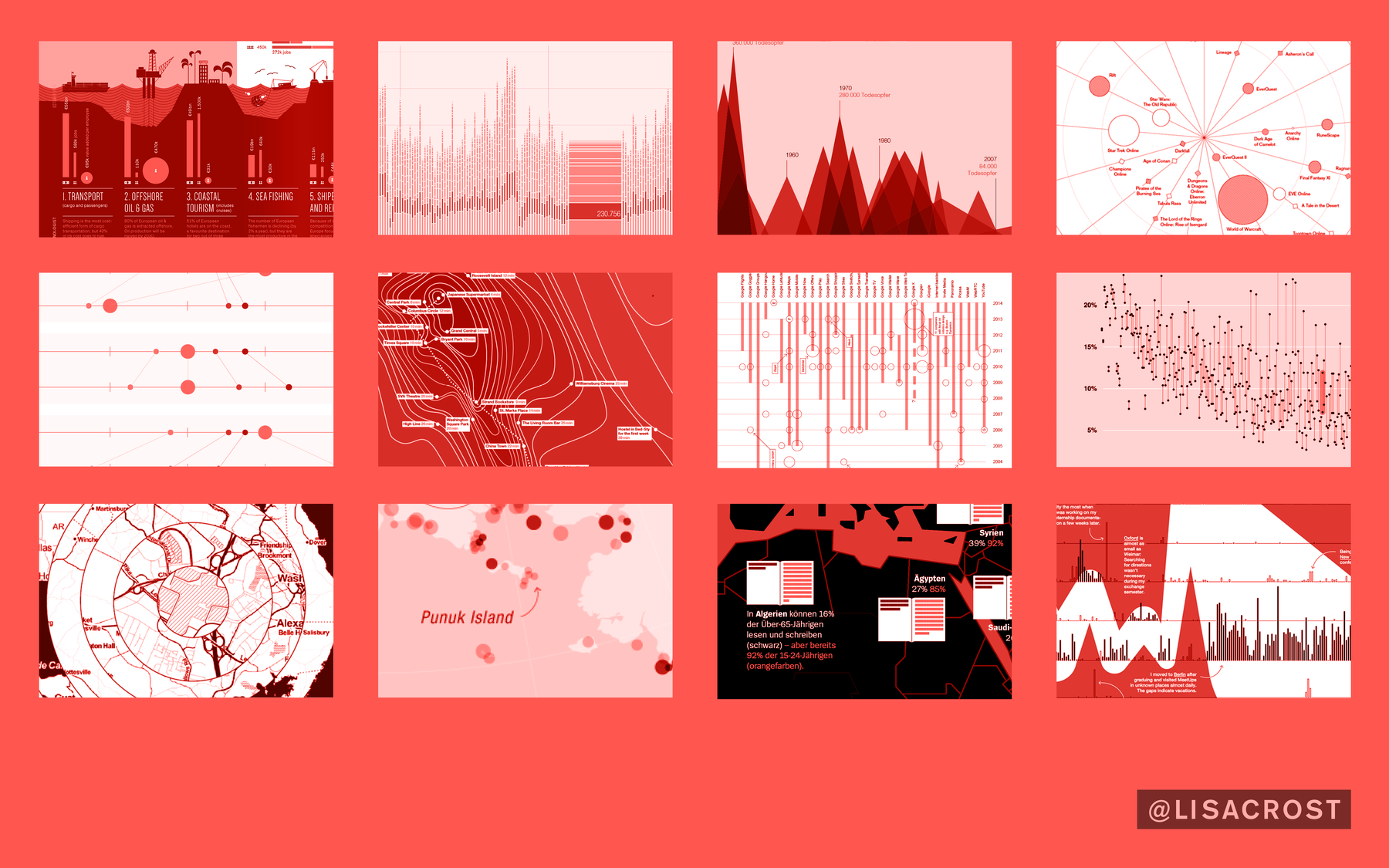

Before I start showing examples; two remarks: First, Map Poetry doesn’t equal Map Art, but is a subset of it. Map Art can include beautiful designed maps that still show an objective overview. But Map Poetry is related to lots of other fields. It seems like a general term for this idea is not found yet. If you want to google for Map Poetry pieces, I recommend googling for any of these terms.

Now I want to show two examples of people bringing the cut-away junks back into geographical maps.

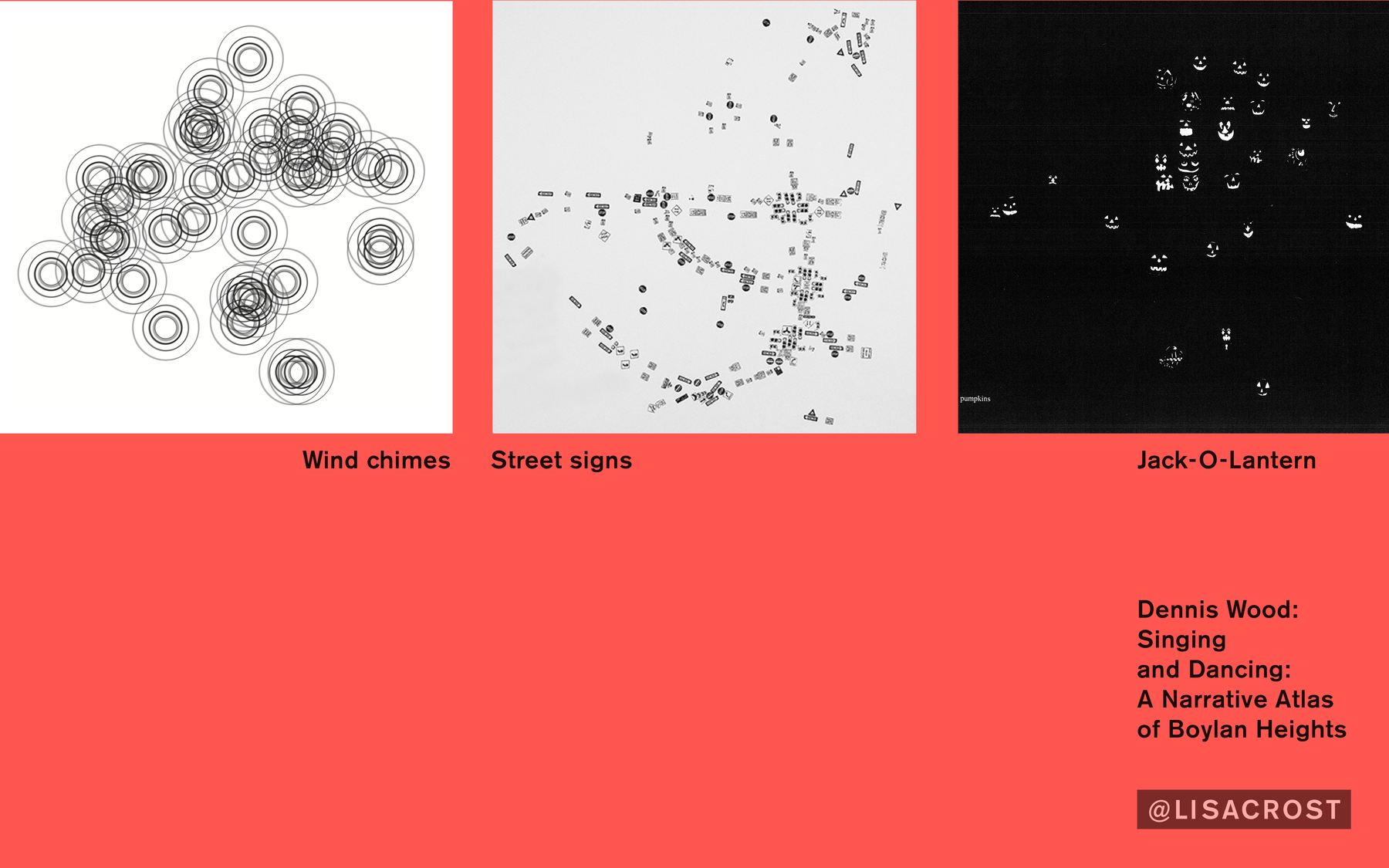

First, Dennis Wood again – and his maps that some of you might be aware of. He and his students mapped a small neighborhood in North Carolina (Boylan Heights in Raleigh). But instead of mapping buildings and streets, they mapped wind chimes, street signs and Jack-O-Laterns – objects that we normally think of as “unworthy” for mapping. His maps point out all the things we cut off when we map the territory:

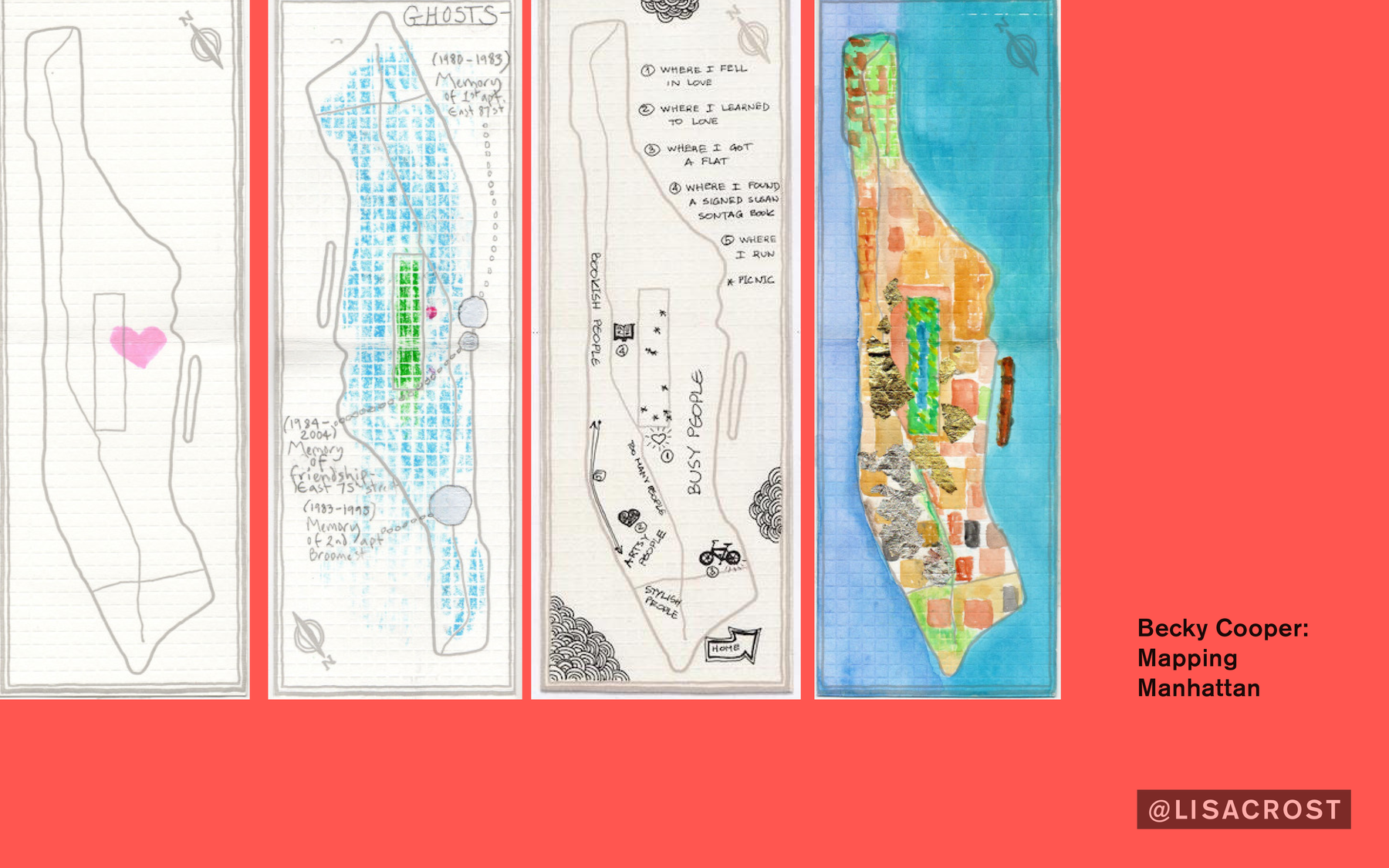

But Dennis Wood didn’t seek out to understand how people perceived this town in North Carolina. Becky Cooper did – for Manhattan. On her blog “Map your memories”, she let’s New Yorkers draw their internal map over a blank map of Manhattan. It shows us that the city doesn’t look the same for everybody, but that everybody associates different memories with it.

However, it gets really interesting when we change geographical maps to show our internal map. Hand-drawn maps like the ones from the United States I showed at the beginning are excellent for that.

More than 3 years ago, when I visited Oxford for the first time, I drew this tiny map. I didn’t plan to use it in a talk one day when I scribbled it, so please excuse that it’s a surprisingly ugly map for a design student:

I show it to point out one detail: This white spot there. Oxford doesn’t have rollercoasters. But this part of town felt like a maze to me, in which I walked in circles. So the map shows how I felt like rather than how it is. But it only shows how I felt in that moment. Half a year later, I returned to Oxford for an exchange semester, and I learnt to navigate that maze. I would have not drawn that loop in my Oxford map after spending a semester there.

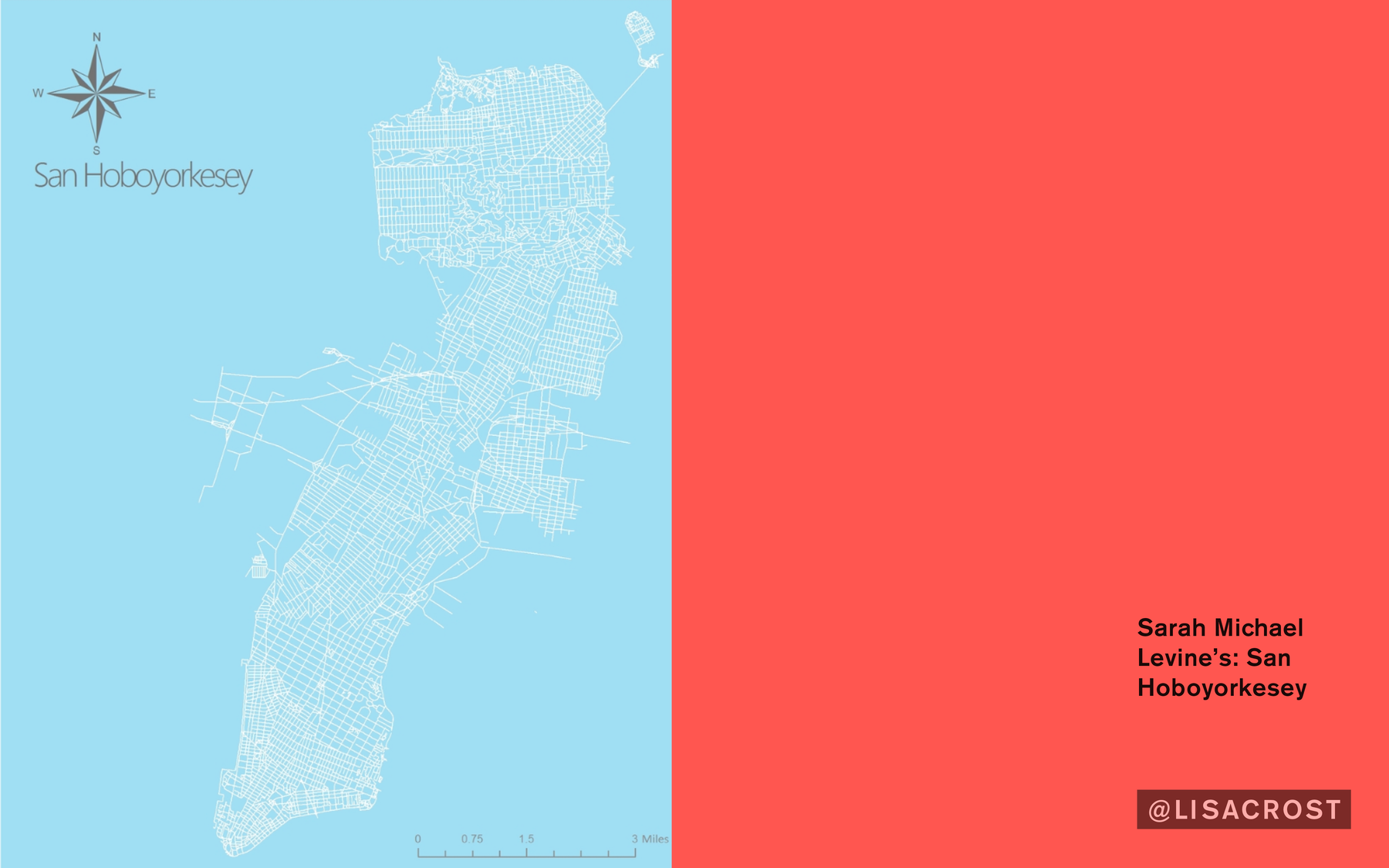

And if we get one step further, we don’t just map the world as it feels – but re-imagine the world based on how we feel. One example for that is Sarah Michael Levine’s “San Hoboyorkesey”, which I really like:

She combines streets from all the cities she has lived in: Hoboken, Jersey City, Manhattan, San Francisco. Sarah created her own personal “Sarah city”, in which she has the best of all the worlds she lived in. “All maps are fictional and sentimental, this one just a little more.”, she writes about her map.

All these Map Poetries are not useful for navigating, which is the main reason that maps are made. You can’t use Dennis Wood’s maps to find an address in this town in North Carolina. You can’t use Becky Cooper’s map to find Times Square. You can’t use my Oxford map to navigate through the tiny alleys. And you can’t use Sarah Michael Levine’s map to find your way from San Francisco to Manhattan.

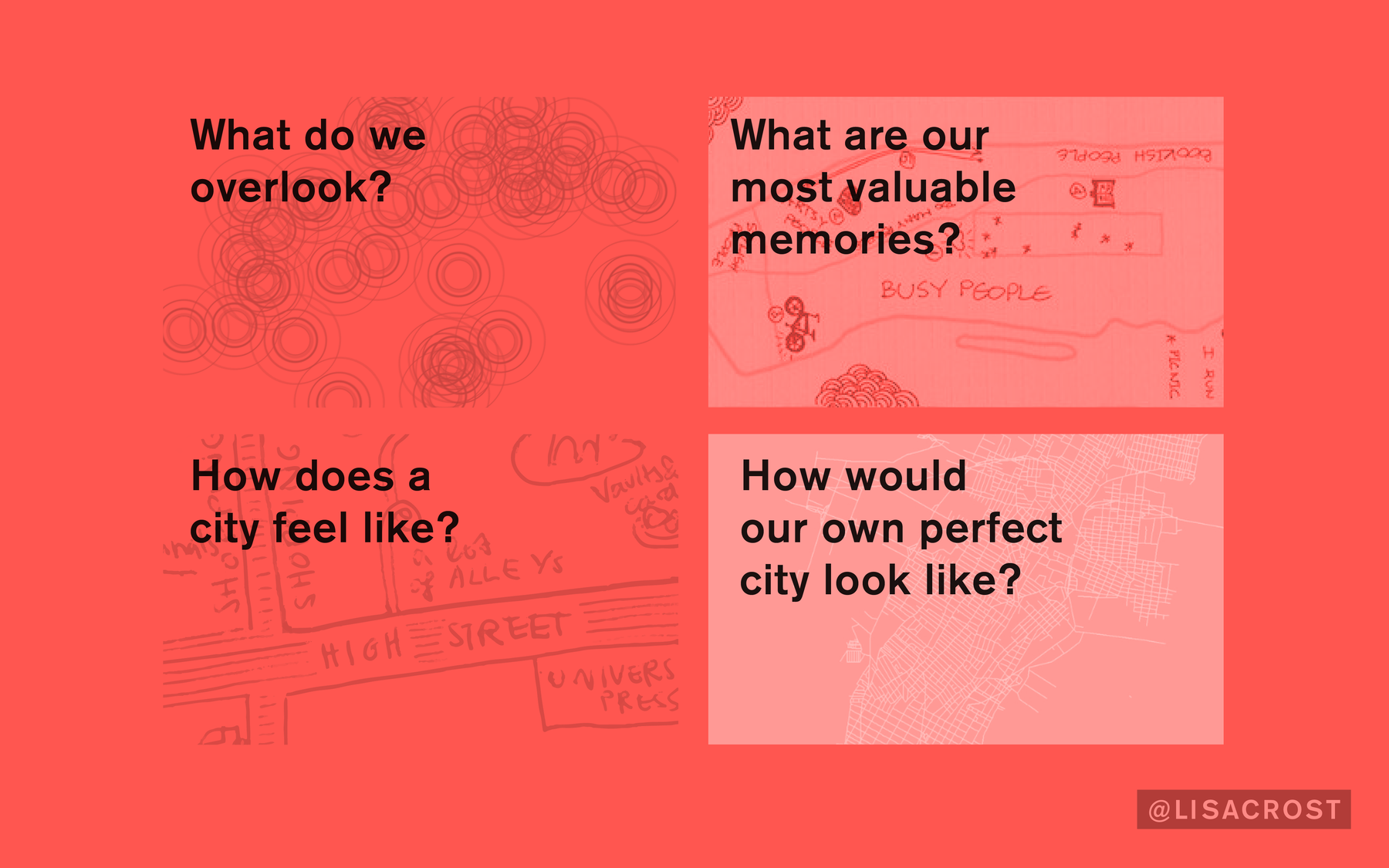

But in my opinion, watching ourselves exploring these maps and comparing our own experience with the experience of the map maker is the real use:

These are just some questions that Map Poetry asks. It can make us more away of all the things that geographical and internal maps cut away. I think we need more of that. I’ll try to create more Map Poetry – and I’d be happy if you’d did the same. So that we can compare them. And then alter our internal maps.