Gosh, the German election system. I still remember learning about it in school. Or rather: I don’t. I was really not interested in politics back then. Of course, I blame my teacher. So every four years I stare at this sheet of paper in the voting booth, trying really hard to remember what it means when I put my cross next to a party’s name.

So what does it mean? What are Germans like me voting for exactly when they’re voting on Sunday? This blog post and an essay spreadsheet I recently created exist solely for the purpose of finding that out. Let’s start (also, you might want to read that blog post on your desktop computer. Sorry.):

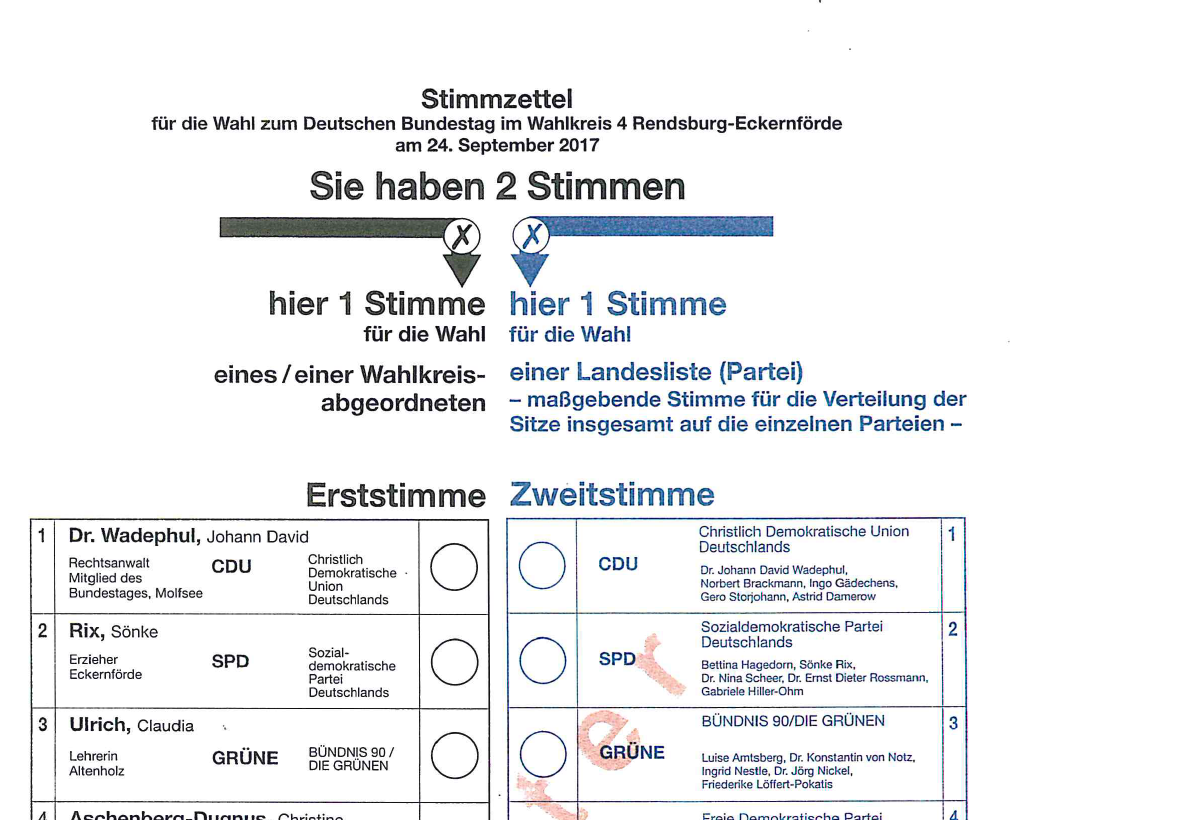

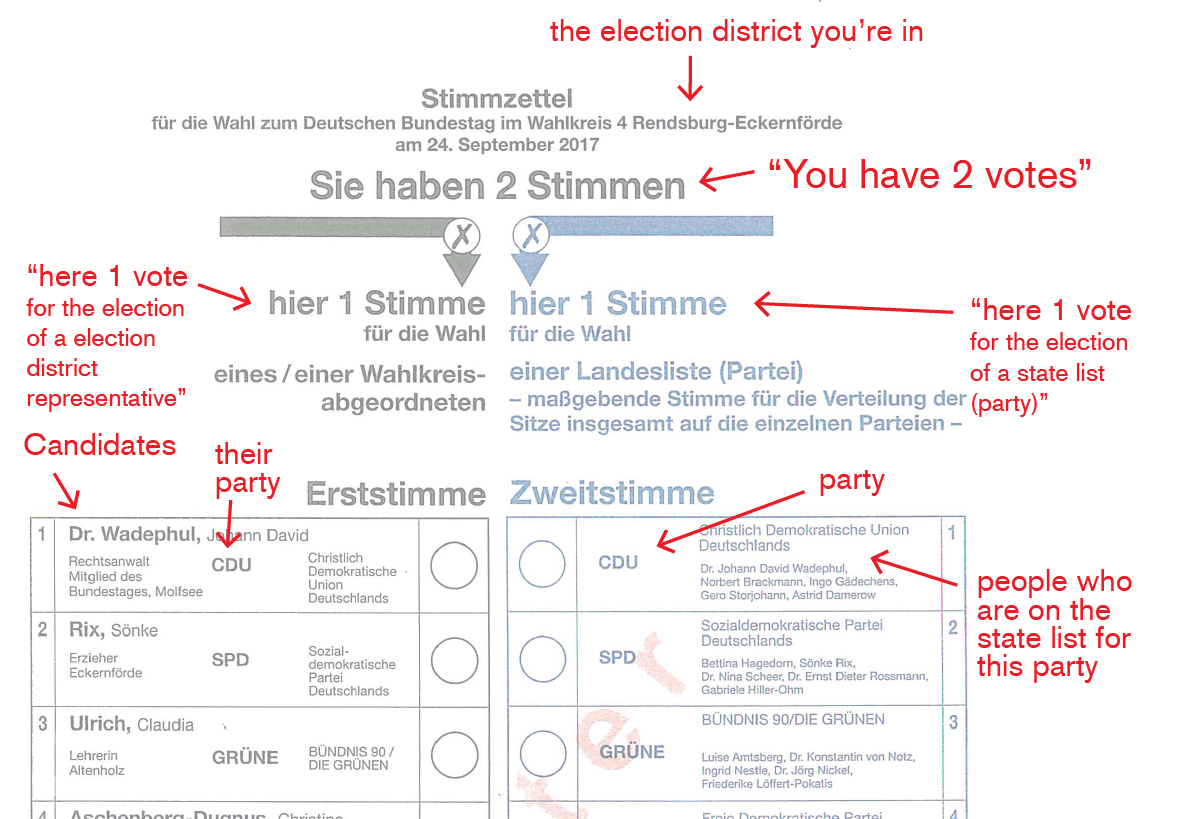

We can’t vote for our chancellor directly. Instead, we are deciding on the approx. 680 people who will move into parliament, and who then will vote for the chancellor and tons of other stuff in the next four years. To decide who these people are, I’ll make two votes on Sunday: The First Vote and the Second Vote.

1 Who?

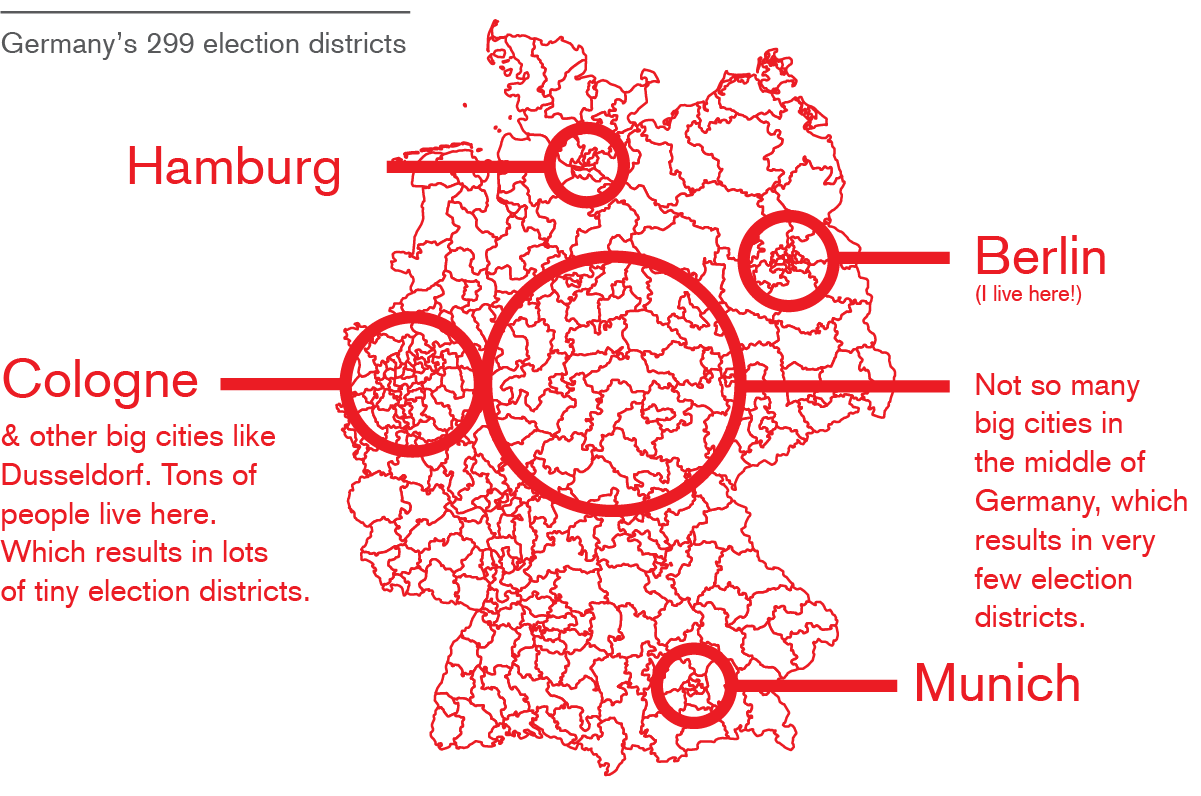

The First Vote is for a person, who is often affiliated with a party and wants to represent my election district in parliament. Germany is currently divided into 299 election districts, which all have roughly the same number of citizens: 280,000 people:

These election districts only become important when they are elections. Most people have no clue about the size of their election districts. And because they only take inhabitants into account, this size can be hugely different. Hamburg with its 1.8 million inhabitants is divided into six election districts. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, another state in the north, has also six election districts. Although the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is thirty times as big as Hamburg when it comes to size, they both have roughly the same number of inhabitants – and therefore the same number of election districts.

The First Vote in the 299 election districts works after a “The Winner takes it all”-system: Only the candidate who gets the most votes in their district will move into the parliament. That means that the parliament is already half full just with the 299 winners from the election districts.

For instance, in the election district “Hamburg Nord”, a candidate for the Christian Democratic party (CDU) won 39.7% of the votes at the last general election in 2013. The 2nd place went to a candidate from the center-left social-democratic party SPD, with 34.8% of the votes. The CDU guy won and got a seat in parliament for sure. The SPD guy went home and cried (or maybe he didn’t. I don’t have any information on that, really.)

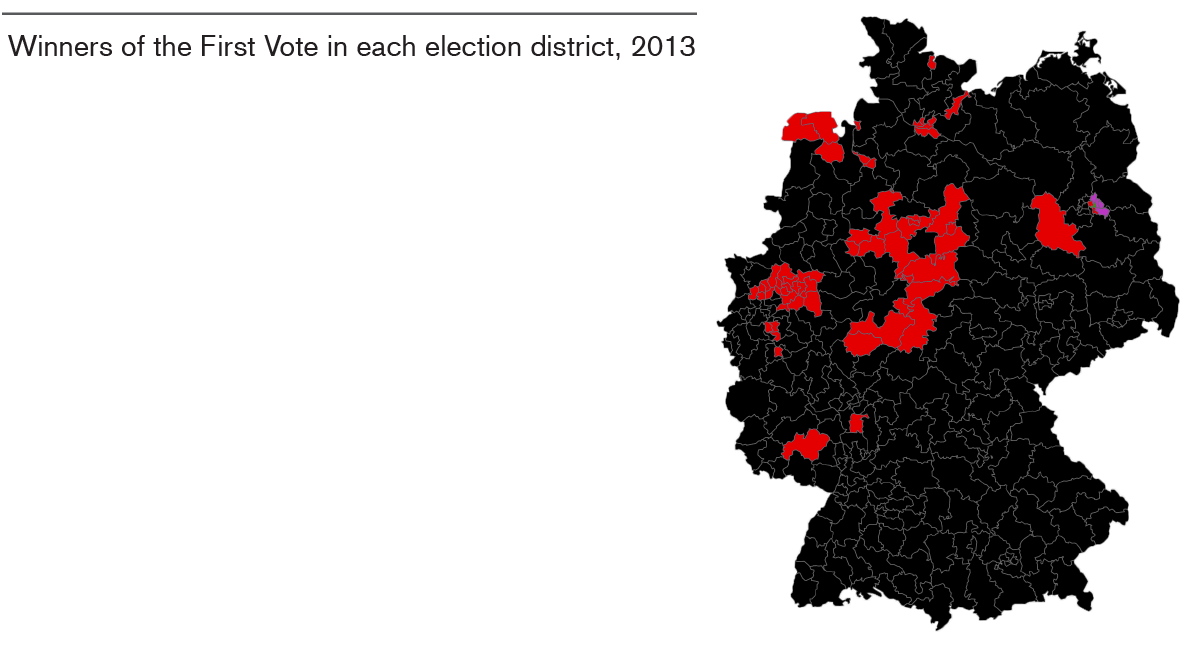

That’s how it looked like in 2013 in all election districts. The election districts are colored according to the party of the person who won this district.

It’s pretty black. Black is the color of the CDU, the party of Angela Merkel. When you look at this map, you’re probably close to thinking: “So the CDU won like…what, 80% of the seats? That’s awful! The poor other parties!”

But don’t pity too early! There is hope: The election districts and the First Vote don’t actually determine how much percent of the parliament seats are taken by which party. That’s the job of the Second Vote. Only with the Second Vote we voters decide what fraction of the seats each party gets. The Second Vote is the reason why the Green party won only one of the 299 election district in 2013 but ended up having 13% of the seats in parliament – and why the CDU didn’t win 80% of the seats, but 40%.

2 How many seats? Also, who else?

The Second Vote is for a party; not for a specific person like the First Vote. Or, to be exact: The Second Vote is for a list of candidates from all parties in my state. In each state in which a party wants to be voted for, the party sends a list of candidates to the election administrator of this state and says: “Please put our party on the ballot in this state.” When I vote for a party with my Second Vote, I actually vote for this state list of the party.

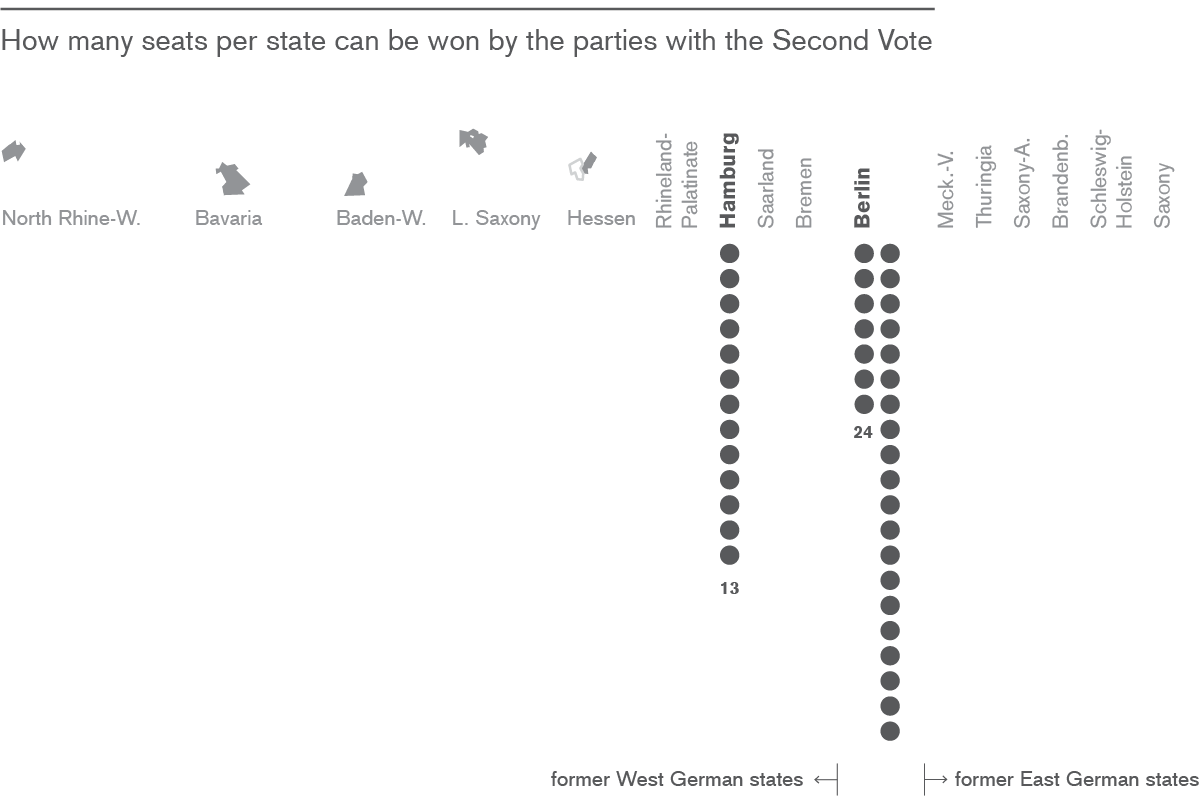

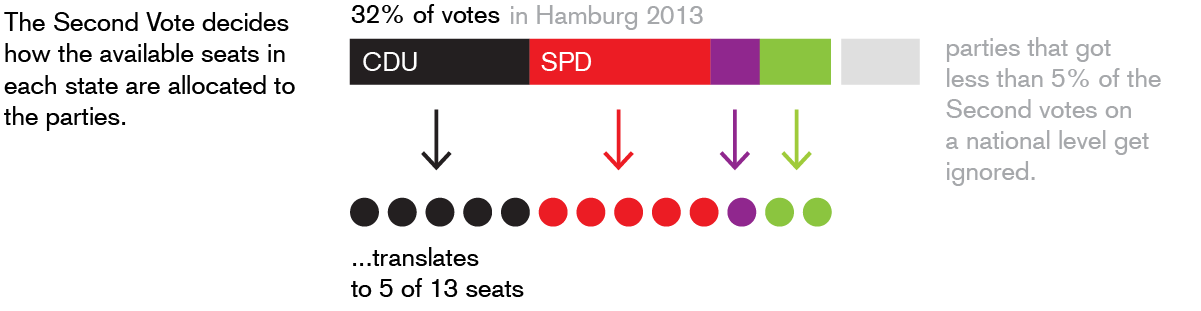

So how do we get from these votes to the seats? Well, in each state, each party can earn a specific amount of seats. The number of seats per state is determined by the number of inhabitants, similar to the election districts. The German election administrator just takes the 598 seats that exist in Parliament and allocates them to the states: Hamburg gets 13 seats, Berlin gets 24 seats, etc.

The more voters in a state vote for a specific party, the more state seats this party gets. The Christian Democratic party won 32% of the votes in Hamburg in 2013, so it gets 32% of the 13 seats for this state (which is…um…5 people 1 ).

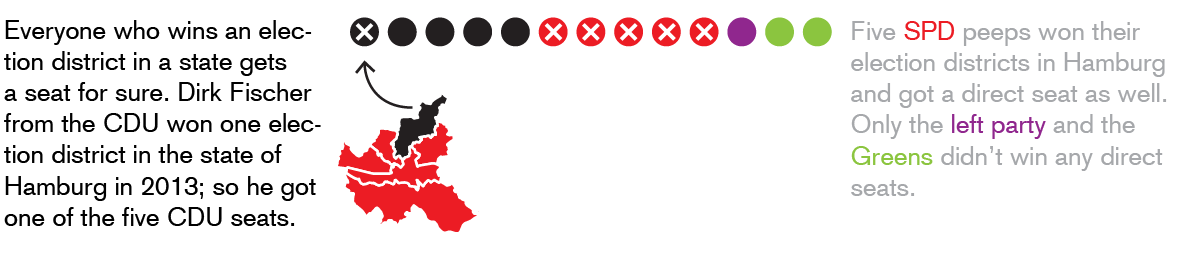

But who are these 5 people? Here, it all comes together. Remember the First Vote? And the guy who won an election district in Hamburg for the CDU? This guy gets one of these 5 seats. That’s the interesting thing: All candidates who win their election districts thanks to the First Vote, are part of the seats which a party wins thanks to the Second Votes.

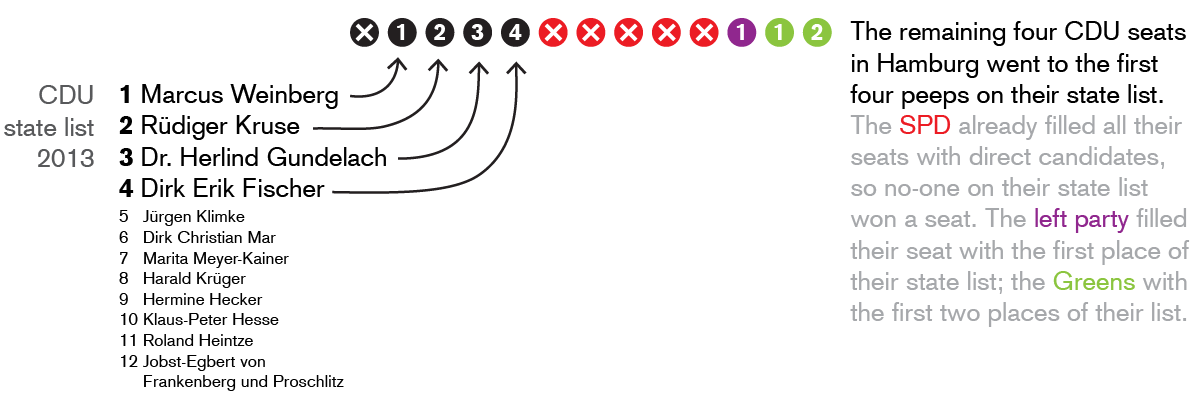

Sooo…that means that the CDU has only 4 seats in Hamburg left to fill with their people. And here, the list that the CDU gave the election administrator earlier makes its appearance. The 4 remaining seats are filled with the first four candidates that are on the CDU-Hamburg-list 2. The fifth person (and sixth person, etc.) is out. Meaning, when a party wants to make sure that the party superstar gets a seat in parliament, they put her at the top of the list – then, if the party gets only one seat in that state, at least the superstar is in.

3 All the seats, in all the states

Here’s a quick summary of what you’ve just learned: Germans have two votes. The First Vote answers the question who will get a parliament seat to represent my election district. The Second Vote answers two questions: How many people of each party will be in parliament for my state? And: Besides the people who got elected directly with the First Vote, who else will get into parliament for each party?

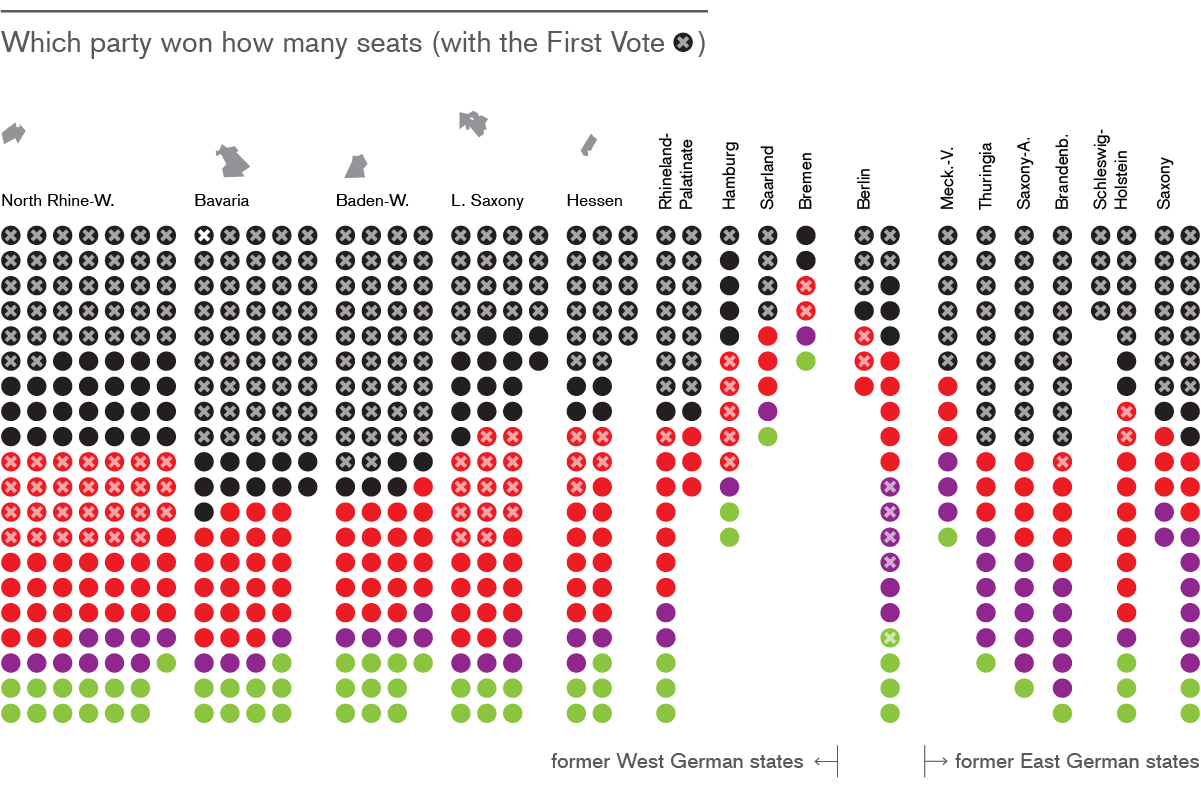

Let’s zoom out. That’s how all the won seats looked like for every single state at the last election:

Here are the most obvious things this overview can show us about the German election in 2013 (these things were true-ish before and will also be true-ish this election):

1 More than any party, the CDU/CSU got almost all their votes in form of election district votes. Only 25% of their seats come from state lists. (In comparison: The Greens had to fill 98.4% of their seats with state list candidates; since only one guy won an election district for them.)

2 The Left party is far stronger in former East Germany than in the former West German states. That’s mostly because it has their roots there: The Left party developed out of an old East German party.

3 The SPD, the Left and the Greens won far more election districts in cities than in rural areas. These three parties won 70% of the election districts in the three city-states Hamburg, Berlin and Bremen; but they won only 18% of the election districts in the rest of the states.

That’s it! Do I feel better about voting on Sunday now? Heck yeah. Here is the ballot again, this time translated into German. If you still don’t have a clue about what it all means, try this very nice visual explainer by the Bloomberg peeps. And please send me an email so I can try to explain it better: lisacharlotterost@gmail.com. Thanks!

-

Here is where it gets a bit tricky. Actually, 32% of 13 seats are 4.2 seats, which is nowhere near 5 seats. But like most countries, Germany has an election threshold. That means that parties don’t get into parliament when they don’t get 5% of all german-wide Second Votes. In Hamburg, people voted a lot for these smaller parties that didn’t end up getting into parliament. In fact, only 86% of the people voted for parties that did end up getting into parliament. That means, we calculate the 32% of this 86% “big-party-voters” – which gives us 37.2% “effective” votes for the CDU-party. And 37.2% of 13 seats are 4.8 seats…which get rounded up to 5 seats. ↩

-

Sigh. I know. I totally left out that very inconvenient but probable case that a party has more direct candidates in a state than it got seats thanks to the Second Vote in that state. These extra seats are called Overhang Mandates and are a pain. If you like pain, you’re welcome to learn everything about them in this spreadsheet essay I built. ↩